SEVEN ReImagined: A Transmedia Storytelling Evolution Proposal

Volume 8, Issue 4, Page No 122-130, 2023

Author’s Name: Joana Bragueza)

View Affiliations

Escola Superior de Tecnologia e Gestão de Viseu – IPV , CIAC – Centro de Investigação em Artes e Comunicação, Universidade Aberta, CEIS20 -Centro de Estudos Interdisciplinares, Universidade de Coimbra, Viseu, 3500, Portugal

a)whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: jbraguez@estgv.ipv.pt

Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 8(4), 122-130 (2023); ![]() DOI: 10.25046/aj080414

DOI: 10.25046/aj080414

Keywords: Digital Media Art, Transmedia Storytelling, Social Art, Sin

Export Citations

“Seven ReImagined” is an innovative transmedia storytelling project that reshapes the exploration of the seven deadly sins in a modern context. Building upon the original artwork “Seven”, this venture incorporates traditional media, digital tools, and the latest immersive technologies to cultivate profound user engagement and interaction. The project’s objective is to enhance understanding of timeless moral themes, encourage self-reflection, and foster communal participation. The project centres around a physical and virtual exhibition (via Metaverse), where the artworks dedicated to each sin invite viewers into a reflective and immersive journey. The inclusion of a confessional booth enriches the narrative by allowing viewers to anonymously express and share their interpretation of their own sins. The journey further extends to a dedicated website and a podcast series, serving as a hub for a comprehensive narrative, providing in-depth information about each artwork, and fostering an engaging global dialogue around these universal themes. Engagement through social media platforms allows the project to reach varied audiences, harnessing the participatory culture of these platforms to stimulate reflections and dialogues. By marrying artistic creativity with technological innovation, “Seven ReImagined”, creates a multifaceted dialogue on ancient moral wisdom in our contemporary society, providing a profound platform for self-reflection and communal participation. The project’s innovation lies in seamlessly blending traditional art with cutting-edge immersive technologies, offering a fresh perspective on ancient moral concepts. Future iterations hold the potential for enhanced sensory experiences, collaborative educational initiatives, data-driven insights, and diverse exhibition formats. In summary, “Seven ReImagined” creatively fuses art and technology, engaging in multifaceted dialogues about ancient moral wisdom. Serving as a platform for introspection and global discourse, the project reaffirms the enduring relevance of fundamental human themes.

Received: 26 June 2023, Accepted: 20 August 2023, Published Online: 26 August 2023

1. Introduction

This paper is an extension of work originally presented in ARTeFACTo2022MACAO conference [1]. The nucleus of this research, “Seven”, was born from an intricate dissection of Bosch’s seminal work circa 1500, “The Seven Deadly Sins”. What started as a historical art review soon revealed a startling modern resonance, prompting us to delve into a myriad of inquiries. The author questions primarily revolved around the adaptability of such archaic themes to address contemporary concerns. What techniques, mediums, or materials could be employed to render these themes relatable to the issues of the present day? The research, therefore, extended beyond the canvas and ventured into the world of past and present sin representation in art, gleaning interpretations from a wide array of artists with diverse cultural and historical backgrounds. The exploratory journey led to an intriguing discovery – the Seven Modern Sins. These served as a linchpin, not only shaping the evolution of “Seven” but also providing a crucial bridge between the historical context of sin and the contemporary social issues the author aimed to probe. This extended paper aims to shed light on the metamorphosis of the artefact into a storytelling project It aims to unravel both the reasons behind and the process of this evolution – why this shift is meaningful, and how is envisaged and actualized this transformation. As we delve deeper into the paper, we first elucidate upon the key concepts that form the bedrock of this article: Digital Media Art (DMA), transmedia storytelling, and Social Art. We then embark on an exploratory journey of the art piece itself. From its creation process and the elements that form its backbone to the interactions it incites with the audience, we cover it all. The narrative then transitions to a comprehensive contemplation of the piece, dissecting its impact, exploring its repercussions, and extrapolating its future potential.

In conclusion, the paper provides a holistic view of the journey of “Seven” so far and ponders over future pathways. It does not merely conclude, but opens up dialogues and questions, paving the way for future work and potential enhancements.

2. Framework

2.1. Media Digital Art – brief considerations

Since the dawn of the 1960s, the world has seen an extraordinary progression of media forms, transitioning from the initial stages of the digital revolution to our current epoch of social media ubiquity. The nomenclature for these technological art forms varies greatly, encompassing labels like Digital Media Art, Media Art, Artemídia (in Brazil), New Media Art, Digital Art, Electronic Art (as termed in Austria), Computer Art, Multimedia Art and Interactive Art. These terminologies emerged during the sixties but only gained prominence in the nineties. In this paper, the term Digital Media Art (DMA) is preferred, primarily due to its congruity with the Portuguese version (the author’s mother tongue) and its expansive nature. DMA, as defined in this context, encapsulates all aesthetic discourse forms that employ digital media and qualitative computational techniques to construct digital or computational artefacts. These artefacts present communicational or informational alternatives [2].

Several movements, such as Dada, Pop Art, Fluxus, Kinetic Art, Minimalism, and more, have served as a bedrock for DMA. For instance, Dadaism, partially a reaction to the industrialization of war weaponry and the mechanical reproduction of text and images, mirrors DMA’s response to the information technology revolution and digitization [3]. Dadaism introduced or altered various concepts, such as authorship, appropriation, and even the definition of art. For example, Duchamp’s “Fountain” was instrumental in challenging these notions. Appropriation practices employed by Dadaists, ranging from renowned artworks like the Mona Lisa to mundane objects [4], resonate within DMA, perhaps due to the simplification brought about by emerging technologies. Such a concept of appropriation is also typical of Pop Art. Many DMA works, akin to Pop Art, are intertwined with the commercial culture [3]. Artists linked with Kinetic Art and Fluxus, such as Nam June Paik, exhibited a keen interest in examining the interactions between media, society, and technology. Their efforts, often materializing as installations and sculptures, manipulated audio-visual technologies to question the authority of mass media. This critical exploration continues in the work of many DMA artists [5], primarily seen in the spheres of Hacking, Tactical Media, and Cybernetic Art. Conceptual Art, according to the authors in [3] significantly paved the way for DMA, emphasizing ideas over the end product. Consequently, DMA is inherently more conceptual in nature. Beryl Graham and Sarah Cook, as cited in [6], argue that new media art is process-centric rather than product-focused. The most relevant practices are fluid, varying in time, space, and authorship. Such a viewpoint suggests that DMA is not preoccupied with aesthetics, like other artistic practices, but rather with functionality.

There are three characteristics that define DMA: processes of interactivity, connectivity, and computability [6]. Another author adds participation to this list [6]. These processes prevail in DMA, not due to artistic or social intentions, but due to the inherent capabilities of the media. The author posits that DMA’s concern is not just process over product, but the process as facilitated by the media. The procedural aspect of DMA, marked by its potential for interaction, connectivity, and participation, adeptly invites various forms of user involvement. These qualities are instrumental in the design of a social artwork, a point that will be elaborated on further in the subsequent sections.

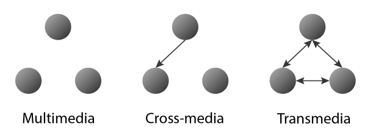

Figure 1: Comparison between Transmedia Storytelling and other storytelling models [13].

2.2. Transmedia Storytelling

Transmedia Storytelling, in short, is stories told through different media; but the concept has nothing simple and there are other adjacent, such as cross media, multiple platforms, hybrid media and intertextual commodity, transmedia worlds, transmedia interactions, multimodality, intermedia; in all, we can perceive an idea of various media, multiple, that perhaps mix, or merge into each other and mainly we can understand that all are based on narratives expressed through a coordinated combination of languages and media or platforms [7]. According to media scholar Henry Jenkins, these concepts align with his theory of media convergence, which creates a content flow across different media channels. This convergence suggests a blurring or complete dissolution of boundaries between different media [8]. In his seminal work, “Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide”, the author [9] argues that media convergence is not just a technological process, but a cultural phenomenon involving new forms of exchanges between producers and users of media content, changing their relationships [10]. the author [9]maps the interrelationship of media convergence, participatory culture, and collective intelligence, three elements essential to the concept of transmedia storytelling. Media convergence, in his view, relates to the flow of content across multiple media platforms, the cooperation between various media industries, and audiences’ migratory behaviour towards the content they desire. This convergence has a potential impact on aesthetics, due to its grassroots expression and transmedia storytelling; on knowledge and education, due to collective intelligence and new media literacy; on politics, due to new forms of public participation; and on the economy, through the web 2.0 business model [10]. Transmedia storytelling can also heighten audience engagement and enjoyment, potentially capturing diverse audiences when execute correctly [8]. The concept entered the public debate around 1999, despite early exploration of transmedia narratives in cinema since the late 1980s [11]. In [12] the author breaks down the concept of transmedia storytelling into ten critical elements: the first, already described above, is related to the fact that transmedia storytelling represents a process where the integral elements of a fiction are dispersed through multiple channels, with the aim of creating a unified and coordinated experience, but each media should give its unique contribution, and the information should not be repeated, that is, one should not take a story and adapt it to the different channels, but use for different for each channel, in this way, there will not be a single source that gathers all the information; in the second point the author refers that transmedia storytelling reflects the economic consolidation of media, this is related to the incentive that a media conglomerate has in spreading its brand or franchise in several media platforms, although this transmedia expansion is an economic imperative, it can enable more expansive and immersive stories; in the third point the author explains that transmedia stories are not based on individual characters or specific plots, but rather, in complex worlds that sustain multiple characters and their stories, this process triggers an encyclopaedic impulse in both readers and writers; in the fourth point the author talks about extensions (never adaptations) referring that this can take on different functions, one of them being to add more realism; in the fifth point he explains the economic potential that transmedia storytelling has by creating multiple entry points for different audiences; in the sixth point it is explained the importance of each part being accessible in an autonomous way and also contributing to the whole, in a unique way, for example, I do not need to watch the Tomb Rider movie to play the game or vice versa; in the seventh point we can understand that the projects that have better results are those where the same artist shapes the story in all the channels involved or in projects where a strong collaboration between teams is fomented; in the eighth point we understand that the transmedia storytelling is the aesthetic ideal for an era of collective intelligence. The transmedia narratives also function as textual triggers that trigger the production, evaluation and archiving of information. The transmedia storytelling disperses information in such a way that no consumer can know everything, forcing him to talk to others, in this way he becomes a hunter and gatherer, travelling between several narratives to form a coherent whole; in point nine we realize that this information is not simply dispersed, they make available functions and goals that readers assume as an enactment of the story in their daily lives; in the last point we understand that some gaps and even excesses allow readers to continue the stories through speculations, they are unauthorized expansions. The reader becomes a creator. On this last point, the author [7] introduced the concept of the “consumer” as the VUP – viewer/user/player. He explains that the VUP transforms the story by using their natural psychological and cognitive abilities to allow the work to surpass the medium and states that it is in the transmedia game and the decentralized authorship that the story is finally revealed, so the VUP becomes the true producer of the work. To the VUP the author proposes adding a “C” to VUP, denoting a creator, thus coining the term VUPC to better represent a transmedia storytelling consumer. From this point on the author will call him VUPC as she believes it is the term that best suits a consumer of transmedia storytelling. The VUPC faces challenges, he requires specific knowledge and technological access to participate in transmedia experiences. This gives rise to the problem of unequal access to technology, which Jenkins calls the digital divide. However, transmedia storytelling can also enhance literacy and accessibility by spreading across multiple channels. Jenkins also states that the culture of participation could diversify content and democratize access to communication channels [10].

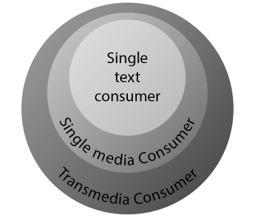

Figure 2: Transmedia World [7].

A significant pitfall of transmedia storytelling is redundancy resulting from improper use. Repetition of content across different channels can cause the VUPC to lose interest, leading to the potential death of the franchise. Therefore, it is crucial to provide new layers of knowledge and experiences that update the franchise and sustain the loyalty of the VUPC [12]

The authors in [13] provide further clarification about what transmedia storytelling is not. They assert that it is neither adaptation, multimedia, nor cross-media. Adaptation does not add anything new and might lead to loss of interest as it merely retells the same story in another channel. Multimedia involves using multiple communication platforms with no mutual relationship, while transmedia storytelling leverages different platforms and creates a mutual relationship between them. On the other hand, cross-media is a marketing technique aiming to market and disseminate the product across multiple platforms, whereas transmedia storytelling tells different aspects of the same story across all channels. In figure 1 we can see a comparison of these three models.

Its suggested [7] that transmedia storytelling has a nested structure, similar to Russian nesting dolls (Matryoshka). This structure can create different entry points and cater to various audience segments. Within this structure, a dedicated fan might navigate from one medium to another, whereas an occasional consumer might have a specific, isolated, and even sporadic interaction. This structure can be observed in figure 2. This author presents four strategies to expand the world of storytelling: creation of micro-link stories which may for example expand the period between seasons with online clips; creation of parallel stories which may reveal themselves at the same time as the macro-story reveals itself, may evolve and become a spin-off; creation of peripheral stories which may be more or less close to the macro-story, may also evolve and become a spin-off; and finally the creation of user-generated content [7].

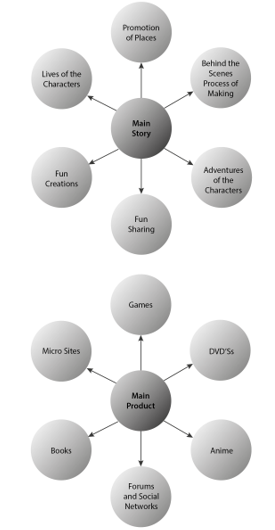

For a transmedia world to be successful, it must have a story that can extend across multiple media, and the design of the world must be thought of as independent, even of the main character. Each episode should maintain the world’s narrative harmony and reveal more than one chain of events adaptable to different media [13]. In Figure 3 the authors describe how each transmedia world is composed of franchised products that contain the main story, which is transferred by “parts”, enriching the story of the world through different channels; and each narrative has its own value. Concluding, [14] offers a definition of a transmedia world as abstract content systems from which a repertoire of fictional stories and characters can be actualized or derived across a variety of media forms. The audience and designers share a mental image of the worldness – a set of distinguishing features of its universe, which can be elaborated and changed over time. This world often has a cult (fan) following across media as well.

2.3. Social Art

The term “Social Art” begins by emphasizing that all art is inherently social and has a role to play in influencing societal norms and values. In the modern world characterized by a process of structural hybridization, the term “social art” gains prominence as a simplified and ambiguous definition that acknowledges the interplay between art and society [15]. In [16] it’s called this art with social approaches “relational aesthetics”, art of social justice, social practice, happenings, interventions or community art, she also mentions that in the last years, there was an increase in the number of artists and art projects that intended to communicate with the public, engaging in a process that included careful listening, thoughtful conversation, and community organizing. Other authors [17] refer to another term – socially engaged art – an art form that believes in the responsibility of art and artists to influence social change. This art form uses a variety of tools, operates outside conventional settings, and often involves artists collaborating with community members. It can address social, political, or economic issues, but it’s not a requirement. The arsenal of resources at the disposal of socially engaged artists is diverse, including conversation, community coordination, shaping and enhancing public spaces (placemaking), guiding collaborative efforts (facilitation), campaigns to raise public awareness, or policy formulation. Additionally, their mediums extend to theatrical productions, art exhibits, musical performances, participatory digital content, and spoken-word poetry, among others. The artistic process is often collaborative, involving artists, community members, other sectors or fellow artists. While the subject matter may sometimes directly address social, political, or economic issues, it doesn’t necessarily have to. The mere act of cultural expression can, in itself, serve as a political act, particularly for groups whose creative voices have been stifled by factors like poverty, cultural assimilation, or systemic oppression. In [18] is traced the roots of socially engaged art back to the 1960s, notably in the incorporation of feminist education into art practice by Alan Kaprow; and the exploration of performance and pedagogy by Charles Garoian and the work of Suzzanne Lacy, among others. The author also mentions that this art falls within the conceptual tradition, safeguarding the issue of the removal of the artist from production that happens in conceptual and minimal art as, in socially engaged art, this cannot happen, the artist is a definitive element. In [19]the discussion is continued, highlighting the 1960s as a pivotal time when artists began to question whether other ways of thinking about art could open the doors that excluded so many from their domain. Although it was understood at the time as a pol itical project, its origin, purpose and values were artistic. More recently the term socially engaged art has been replaced by social practice. This term excludes reference to art, thus avoiding evocations of the role of the modern artist as a visionary and the postmodern version of the artist as a self-conscious critical being. Choosing the term “participatory art,” the author[19] sets it apart from community art, explaining that participatory art involves collaboration between professional and non-professional artists, while community art leans towards an emancipatory social commitment.

Figure 3: Nested structure [13].

In 1991, it is introduced another term – New Genre Public Art – which generally refers to public art with an activist nature, often created outside the institutional structure and which places the artist in a direct relationship with the public, while addressing social and political issues. In this paper has been choosing to use the term Social Art as the author believes it is broader and in this way can encompass all the others. Regardless of the term used, and the form this art can take, there are according to [17] three essential components: intentions (what one wants to do and for whom); skills (both artistic and social); and ethics. However, there are works that are not made with social intention but are ultimately beneficial. There is a broad consensus among researchers that community arts have a number of benefits, for example: Living As Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991-2011 [16] shows us several case studies, although it is only descriptive, it gives us a very comprehensive overview of projects done in different places around the world; Art and Upheaval: Artists on the World’s Frontlines by Cleveland where it investigates how art can be used to heal and rehabilitate communities affected by different social problems; How Arts Impact Communities [20] which addresses the problem of how to assess positive and negative impacts on the community; there are also several municipal reports as well as guidelines for initiating projects. For example, Making Art with Communities: a work guide [21], besides giving us information about different projects, has some guidelines to orientate the creation of a project: all projects should promote and incorporate: social inclusion and equality – respecting diversity and inclusive of differences and needs; active participation; creative collaboration; community and/or collective ownership; transparency, clear processes and honesty; a clear understanding of expectations, process and context; reciprocity – sharing, caring and generosity; respect and trust; empowerment of participants; development of skills, knowledge, capacity and capability; and a shared understanding that everyone has rights and responsibilities. They have also created a guide to help us evaluate the impact of these projects: Evaluating Community Arts and Community-Well-Being.

2.4. Intersecting Pathways: The Synergistic Alliance of Digital Media, Transmedia Storytelling, and Social Art

Over the past decade, the methods used by communities and community organizations to bring attention to their struggles and foster change have evolved rapidly. Digital technology plays a pivotal role in this progress, offering a conduit for the swift and widespread creation and propagation of stories. Transmedia storytelling has emerged as a cutting-edge practice in this context, with several projects already harnessing its potential, consciously or not. Transmedia storytelling redefines the narrative landscape and reshapes the way storytellers engage their audience. It provides platforms for groups that have been marginalized or overlooked to voice their narratives in the public sphere. This socially-driven application of transmedia storytelling has given rise to a new term – Transmedia Activism. The authors who first introduced the term [22], describe it as a fusion of story, community, and collaboration. It harnesses the power of storytelling distributed across multiple mediums, offering myriad perspectives that shed light on social, political, and cultural contexts, thus potentiating effective social action.

Let’s consider some prominent projects in this field:

- WWO (World Without Oil) is an interactive game engaging participants across demographics in employing ‘collective imagination’ to address a real-world issue: the peril our unchecked oil consumption poses to our economy, climate, and quality of life.

- Wasteland, conceptualized by Maria Cristina Finucci, presents a series of interrelated actions across varied locations. Finucci establishes a ‘state’ composed of ocean-drifting plastics – The Garbage Patch State – replete with the trappings of nationhood, including a flag, constitution, citizens (plastics), a national day (April 11), a passport, and even a Facebook page. This interactive piece, offering postcards or even nationality, brings the environmental impact of plastic waste to the fore in an engaging and unconventional way.

- HIGHRISE is a collaborative documentary project spanning several years and various media formats. Since its inception in 2009, HIGHRISE has produced over 20 unique projects encompassing interactive documentaries, mobile productions, live presentations, performances, installations, site-specific intervention projects, and films.

These examples are just the tip of the iceberg, serving to underscore the real and potential synergies between transmedia storytelling and Social Art, with numerous artists and non-artists already making this collaboration a reality. Active participation is a growing concern among sponsors and artists, and the transformative potential of technological advancements to catalyse and amplify new forms of engagement cannot be overlooked. In [6] the author cites a report commissioned by Arts Council England, Arts & Business, and Museums, Libraries and Archives Council which acknowledges the paradigm-shifting power of the internet to revolutionize how we engage with, share, and create artistic content. It enriches the real-life experience without supplanting it. The report also points to the myriad opportunities now available for arts and cultural organizations to expand and intensify audience engagement via the internet, not only as a marketing and audience development tool but also as a core platform for content distribution and delivery of immersive, participatory, and fundamentally new artistic experiences. Although transmedia storytelling is not confined to the internet, the latter is a potent conduit for such narratives. The author is confident that transmedia storytelling will extend both the reach and the commitment of all involved, creating a more engaging and dynamic sphere for artistic and social expression.

It’s evident that DMA and Social Art also exhibit crucial overlapping features in their practices, such as collaboration and participation. Moreover, the author posits that several primary characteristics of DMA can greatly enhance participation and expand reach. While DMA practices do not explicitly aim for social involvement, numerous DMA practices offer platforms for exchange and collaboration between users; they unite communities by making networking and exchanges easier [6]. They also serve as avenues for political activism or advocacy, leveraging internet, mobile, networking technologies, and social media. They offer media education and unrestricted software access and expertise, thereby contesting the capitalist control over proprietary platforms and ‘closed’ systems (for instance, open-source art pieces and art hacking workshops). Furthermore, they stimulate collective creativity by offering platforms that foster active participation and personal contributions (like community-driven, user-generated projects).

Although DMA is not inherently socially involved, it encompasses approaches and procedures that bear relevance to socially engaged practices. Political participation is intimately tied to new media participation, and there are several correlations between “new media art” and “socially engaged art” [6]. This suggests an intriguing convergence of practices and goals, highlighting how digital media can be a conduit for socially engaged art. By building on shared characteristics such as collaboration and participation, it’s possible to create a more dynamic, inclusive, and impactful practice. It shows the power of digital media to bring communities together, challenge existing structures, and create new, shared experiences. Thus, while not explicitly socially engaged, DMA’s emphasis on participation, collaboration, and open access makes it a natural partner for Social Art in the pursuit of collective creativity and social change.

In conclusion, the dynamic alliance between DMA, transmedia storytelling, and Social Art presents an exciting new frontier for creative expression, social activism, and community engagement. In the digital age, technology has become the enabling force for communities and organizations, allowing them to raise awareness of their causes and instigate change. Transmedia storytelling, a key innovation in this digital revolution, offers a fresh approach to narrative that engages audiences on a deeper level and gives voice to groups who were previously marginalized. When viewed through the lens of Social Art, transmedia storytelling transforms from just a method of conveying stories across multiple platforms, to a mechanism for empowering communities and driving social change. In essence, transmedia storytelling and Social Art converge to form ‘Transmedia Activism’. The birth of this term testifies to the powerful potential of this innovative approach, as it blends storytelling, community engagement, and collaboration to spark significant social action. On the other hand, DMA, while not inherently socially engaged, showcases various approaches that are strikingly relevant to social practices. The emphasis on participation, collaboration, and open access in DMA practices resonates deeply with the principles of social art.

Figure 4: Detail of a panel (exhibited at “Cartografias na cidade”, Quinta da Cruz, Viseu).

Therefore, it’s evident that digital media, transmedia storytelling, and Social Art are not just individual entities. They are interconnected threads of a larger narrative, each amplifying and enhancing the others. Together, they have the power to reshape the cultural and artistic landscape, fostering a more inclusive, participatory, and socially engaged environment. This convergence of practices and goals signifies a promising future where art is not confined to galleries or concert halls but is ingrained in the fabric of our communities. It foretells a world where stories are not just told but lived, and where art becomes a catalyst for social change. The future of art is here, and it’s digital, transmedia, and profoundly social.

3. The Seven Artefact – old version

“Seven,” the interactive art installation, probed the correlation between DMA and Social Art by using digital art techniques to convey a socially significant message. This message was designed to raise awareness about various contemporary, worldwide issues. The installation is crafted from a mix of materials and techniques: acrylic is utilized as the main material for its transparent quality, enabling the central content – a blend of resin, pigment, and acrylic paint – to appear as if it’s gradually disappearing, thus producing a dreamy aura; around this acrylic structure is a chain of LEDs that illuminates each panel with one of the seven colours from the solar spectrum; the base of this structure houses a sensor that activates both the LEDs and audio, ensuring that these elements are only triggered when a user is within one meter of the panel. An Arduino is also incorporated into the structure to ensure the entire process of LEDs and audio activation, and their respective colour and musical note. The light from the LEDs and the sound contribute to an immersive experience. The LED lights add to the dreamy ambience, while the sound is designed to elicit a slight emotional disquiet. Positioned beneath the painting is a tag with the panel’s title, representing one of the original seven deadly sins. The tag carries a retro design, juxtaposing most of the materials used. This concept of duality is omnipresent: good versus evil, old versus new, tradition versus technology, the monochrome painting against the coloured LEDs; the geometric contrasts, the organic against the inorganic, and so forth. To view a brief AR video, the user must install an app. Each video visually depicts a mortal sin; all the videos are created using 3D animation and maintain a transparent background to ensure the panel remains visible. In Figure 4, you can observe one of the panels and the tag that explains how to install the app. At the conclusion of each video, the corresponding modern social sin to the ancient one is revealed. The correlations between the ancient and modern sins, colours, and sounds can be viewed in Table 1, while Figure 5 showcases these correlations with the visual composition located at the centre of the structure.

The user must navigate the journey in the sequence presented in Table 1 and Figure 5. The final sight after viewing all the panels will be the question – WHAT WAS YOUR SIN TODAY? – intended to incite self-reflection as the culmination of the journey. It’s a period of reflection where all your senses relax after the immense stimulation they have encountered thus far. This message should appear in a minimalistic, white area with dim lighting and silence, encouraging this contemplative moment. The use of the English language is to ensure the artwork is accessible to users of various nationalities. The pursuit of universality is also evident in other components such as light and sound. Different users will interact with different aspects; it isn’t crucial for them to grasp all elements. For instance, a visually inclined user may focus on the painting and colours, while a user with a keen ear may discern the variety of sounds. This characteristic also amplifies the installation’s accessibility.

Table 1- Sins Associations

| Sin | Colour | Musical note | Modern sin |

| Wrath | Red | Do | Drug trafficking |

| Gluttony | Orange | Re | Violation of the fundamental rights of human nature |

| Greed | Yellow | Mi | Creating poverty |

| Envy | Green | Fa | Obscene wealth |

| Lust | Blue | Sol | Immoral scientific experimentation |

| Sloth | Indigo | La | Destroying the environment |

| Pride | Violet | Ti | Genetic manipulation |

4. Seven ReImagined

Building upon the foundation laid by the original “Seven” installation, its evolution into a transmedia storytelling project titled “Seven ReImagined” represents the next logical step in its journey of digital and Social Art exploration. “Seven ReImagined” embodies the principles of DMA, Social Art, and transmedia storytelling to create an immersive, interactive, and comprehensive narrative experience across multiple platforms and channels. The advancements implemented within “Seven ReImagined” seek to adapt to the evolving digital landscape, as well as further the reach and impact of the artwork’s core message – prompting reflections on morality and our roles in contemporary global issues. In this iteration, the physical panels of “Seven” form the heart of the experience, but the narrative’s reach is extended via digital platforms and interactive technologies. The goal of this evolved project is to maintain the original’s ethereal and emotionally impactful essence, whilst enhancing accessibility, interaction, and reach to engage a broader audience and facilitate deeper engagement.

Figure 5: Visual representation of the associations described in table 1.

The first major change in “Seven ReImagined” is the introduction of virtual reality (VR). Whereas the original required users to be physically present to fully interact with the installation, the new VR world will enable a remote yet immersive engagement. The project will employ the Metaverse – a collective virtual shared space that is being facilitated by the convergence of virtually enhanced physical reality and physically persistent virtual space – as its hosting platform. Metaverse is essentially a network of 3D virtual worlds focused on social connection, which fits perfectly with the Social Artt objectives of “Seven ReImagined”. As a VR-enabled project, “Seven ReImagined” could transcend geographical and physical limitations, making the installation accessible to a global audience. In this VR exhibition, the users, via their avatars, can navigate the virtual gallery that houses the “Seven ReImagined” panels. The panels would be 3D digital reproductions of the original panels, retaining the design and detail, including the sense of depth provided by the acrylic, resin, pigment, and LED components. Creating this virtual exhibition would involve the use of VR development platforms such as Unity or Unreal Engine, both renowned for their VR development capabilities. The development would also require extensive use of 3D modelling tools like Blender for creating both the gallery environment and the 3D digital reproductions of the panels. This shift to VR would enhance the user’s ability to engage with the exhibit, adding an extra layer of depth to the overall experience. The user would be able to physically look around the gallery, approach each panel, and engage with it as if they were physically present.

A second change will be made in the audio experience. Actually, this point was a concern since the beginning, the author was never satisfied with the audio experience it seem to be rough and break the meditation process. An immersive audio experience will be developed using binaural audio technologies to create 3D soundscapes. This technique, proven to enhance immersion in projects like BBC’s The Turning Forest VR experience, directed by Oscar Raby and written by Shelley Silas, will ensure remote users also experience the unsettling yet thought-provoking sounds designed for each panel. The immersive audio environment will translate well to the VR platform as well. Spatial audio techniques could be employed to create a soundscape that adapts to the user’s movements, enhancing the immersion and interactivity of the VR experience.

In addition to the primary exhibition, the VR environment could host live events such as guided tours, talks, or interactive sessions with the creators, enriching the user’s understanding of the artwork. Similarly, real-time social features could be added, allowing users to visit the exhibition together with friends, discuss their interpretations, or even meet new people. Incorporating VR into the “Seven ReImagined” project aligns with the increasing trend of creating VR experiences in the art world. Major institutions like the Tate Modern and the Smithsonian American Art Museum have created VR exhibitions, revealing the potential of VR to revolutionize the way we interact with art. By embracing this technology, “Seven ReImagined” positions itself at the forefront of this digital transformation in art, enhancing its reach, accessibility, and impact.

Enhancements will be brought to the physical exhibition, transforming it into a network of eight distinct spaces. Each space will be dedicated to a particular sin, culminating in a final reflective room. The captivating centrepiece of each sin room will be the paintings from the panels of Seven, but they will stretch across a wall, operating as a meditative mandala. The atmospheric lighting in each room won’t be provided by LED strips but by room-wide illumination, imbuing each space with a colour representative of the sin it is hosting. This adjustment adds depth and character to each room, immersing the viewer in a coloured ambience. For contemplation, comfortable seating will be scattered throughout each room, ensuring adequate personal space for introspection.

The concluding room will present the thought-provoking inquiry – WHAT WAS YOUR SIN TODAY? – now, the participant will have the opportunity to respond. This room will house three confessional booths where visitors can reflect on their personal transgressions and record their responses via a compact screen and keyboard. All contributions will be gathered anonymously and amalgamated on a dedicated website, fostering an anonymous community of introspection. Upon leaving the final room, guests will be encouraged to extend their engagement through the website or the digital platform. This digital extension, built within the Metaverse, will mirror the physical exhibition, including the distinctive spatial organization and the introspective confessional booths.

Given that the Augmented Reality component of the physical exhibition proved to be somewhat distracting, causing some visitors to forego its use, this component will be omitted in the remodel. Consequently, the 3D videos reliant on this technology will be similarly removed.

In order to amplify the transmedia experience, a bespoke “Seven ReImagined” website will be established as the nexus for the wider narrative. This platform will offer detailed insights into each panel, interviews with the creator, exclusive behind-the-scenes content, and a digital confessional booth for online participants to share their thoughts.

Furthermore, a podcast series will be introduced, following the concept popularized by Lance Weiler in his transmedia project “Hope is Missing.” This auditory narrative will delve deeper into the exploration of each sin and its modern equivalent, featuring guest discussions from a diverse range of experts, including psychologists, philosophers, historians, social activists, and fellow artists.

In the spirit of audience inclusivity, “Seven ReImagined” seeks to effectively infiltrate the digital landscape populated by younger audiences through a robust social media strategy. Utilizing platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter, the project will introduce eye-catching animations and teasers, each crafted to embody one of the seven deadly sins in its modern form.

For Instagram, short, visually stimulating videos will be created to grab the audience’s attention. Each sin will be represented by a unique colour scheme, symbolic imagery, and brief text overlays to explain its modern interpretation. The Instagram strategy will also include engaging stories and interviews or behind-the-scenes content.

On TikTok, we will harness the platform’s algorithm and hashtag system to reach new audiences. Each sin could have its dedicated ‘challenge’ where users are prompted to create content related to their interpretation of that sin. For instance, for the sin ‘Sloth’ equated with ‘Destroying the environment’, the challenge could be for users to share their eco-friendly habits or initiatives.

Twitter’s approach will focus on initiating a dialogue around these sins. Scheduled tweet threads detailing the thought process behind each sin and its current interpretation, engaging Twitter polls, and Q&A sessions could be a part of this strategy.

The pre-existing 3D videos from the original “Seven” can be repurposed as short video snippets or GIFs, offering the audience an immersive sneak peek into the project. They can be used as engaging visual content on any of these platforms, encouraging shares, comments, and reactions.

The audience will be motivated to participate by tagging friends, sharing their own insights, or creating related artwork using a specific project hashtag, fostering a global online community centred around the themes presented by “Seven ReImagined”. Each social media platform will serve a unique function in this comprehensive strategy, harnessing its specific features and user behaviours to further the reach and impact of the project.

5. Final Considerations and Future Work

The Seven ReImagined transmedia project powerfully combines traditional and digital media, physical and virtual reality, to deliver a profound exploration of the timeless seven deadly sins and their contemporary counterparts. The project marries artistic creativity with technological innovation, effectively facilitating user interaction and engagement. The use of VR technologies in a Metaverse environment creates an immersive digital exhibition that transcends geographical boundaries. The project then seamlessly extends the interaction to the web, harnessing the power of digital platforms to cultivate a global conversation around these universal human themes. The conceptual evolution of the exhibition to encompass eight rooms, each dedicated to a particular sin, facilitates a more profound interaction with the user. The meditative environment, enhanced by colour-coded ambient lighting, encourages introspection and dialogue about these shared moral concerns. The inclusion of a confessional booth, both in the physical and virtual exhibition, is a powerful narrative device allowing for anonymous expression and communal participation. It moves beyond observation and contemplation, to action and contribution. In contrast to the original Seven, which relied on the use of AR technology, this new direction takes advantage of the growing prevalence and acceptance of VR technologies and Metaverse platforms. The decision to shift from AR to VR and Metaverse came after observing that the task of installing an AR app distracted many visitors and disrupted the immersive experience.

The dedicated website and the podcast series further contribute to a transmedia narrative that extends beyond the physical or virtual exhibition. It allows for a more nuanced exploration of the themes, the artistic process, and the societal implications. The engagement on social media platforms allows the project to reach and interact with a younger audience in a space they are most comfortable in.

Reflecting on the project’s evolution and learning experiences, it is clear that “Seven ReImagined” has significant potential for further development and expansion. Firstly, future iterations could consider enhancing the VR experience through the inclusion of additional sensory stimuli. Haptic technology, for instance, could make the interaction with the artwork more tangible and immersive. Collaborations with other artists, historians, or technologists in these expansions would also create a more diverse and richer narrative. Secondly, the project could partner with educational institutions and educators, to use “Seven ReImagined” as a pedagogical tool. This could be particularly relevant for subjects such as art, philosophy, ethics, and digital media. The project can stimulate insightful discussions, enable immersive learning experiences, and inspire creative student projects. Thirdly, the confessional data collected anonymously from different platforms could be analysed and used for research purposes. It could provide valuable insights into our shared moral concerns and dilemmas, our understandings and interpretations of the sins, and how they vary across cultures and societies. Lastly, the project could experiment with alternative exhibition formats. Pop-up exhibitions or installations in public spaces could invite unexpected encounters and interactions, reaching a wider audience.

Overall, “Seven ReImagined” is not only a testament to the exciting possibilities of transmedia storytelling and digital innovation, but it is also a reminder of the enduring relevance of ancient moral wisdom in our complex modern world. By continually adapting and evolving, it can continue to inspire, provoke, and engage audiences around the globe in a deeply human conversation.

- J. Braguez, “SEVEN: a socially engaged digital media art installation,” 022 Third International Conference on Digital Creation in Arts, Media and Technology (ARTeFACTo), 2022, doi:10.1109/ARTEFACTO57448.2022.10061262.

- A. Marcos, “Média-arte digital: arte na era do artefacto digital/computacional,” InVISIBILIDADES: Revista Ibero-Americana de Pesquisa Em Educação, Cultura e Artes, 7, 4–8, 2014.

- M. Tribe, R. Jana, New Media Art, Taschen, Germany, 2007.

- T. Laurenzo, DECOUPLING AND CONTEXT IN NEW MEDIA ART, Universidad de la República Montevideo Uruguay, 2013.

- M. Connolly, L. Moran, S. Byrne, WHAT IS_(New) Media Art?, Education and Community Programmes, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Jul. 2022.

- M. Chatzichristodoulou, “New Media Art, Participation, Social Engagement and Public Funding,” Visual Culture in Britain, 14(3), 301–318, 2013, doi:10.1080/14714787.2013.827486.

- C. Scolari, “Transmedia Storytelling: Implicit Consumers, Narrative Worlds, and Branding in Contemporary Media Production,” International Journal of Communication, 3(21), 586–606, 2009.

- A. Toschi, “The Entertainment revolution: Does transmedia storytelling really enhance the audience experience? Working paper,” in Convergence Culture and Transmedia Storytelling, California State University, Fullerton, 2009.

- H. Jenkins, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, New York University Press, New York, 2006.

- V. Navarro, “Sites of Convergence: an interview with Henry Jenkins,” CONTRACAMPO – REVISTA DO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM COMUNICAÇÃO – UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL FLUMINENSE, 21, 2010.

- C. Lacalle, “As novas narrativas da ficção televisiva e a Internet,” Matrizes, 3(2), 79, 2011, doi:10.11606/issn.1982-8160.v3i2p79-102.

- H. Jenkins, “Transmedia Storytelling 101,” 2007.

- E. Gürel, Ö. Tığlı, “New World Created by Social Media: Transmedia Storytelling,” Journal of Media Critiques, 1(1), 35–65, 2014, doi:10.17349/jmc114102.

- L. Klastrup, S. Tosca, “Transmedial worlds – Rethinking cyberworld design,” Proceedings – 2004 International Conference on Cyberworlds, CW 2004, 409–416, 2004, doi:10.1109/CW.2004.67.

- C. Madeira, “A (in) visibilidade da arte social,” Revista Arte & Sociedade, 2, 33–44, 2011.

- N. Thompson, Living As Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991-2011, MIT Press, Cambridge, 2012.

- A. Frasz, H. Sidford, Mapping the Landscape of Socially Engaged Artistic Practice, Helicon Collaborative, 2017.

- P. Helguera, Education for Socially Engaged Art: A Materials and Techniques Handbook., Jorge Pinto Books, New York, 2011.

- F. Matarasso, Uma Arte Irrequieta, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisboa, 2019.

- J. Guetzkow, “How the Arts Impact Communities: An introduction to the literature on arts impact studies,” Working Papers, Princeton University, School of Public and International Affairs, Center for Arts and Cultural Policy Studies, 44, 2002.

- Vic Health, Arts Access, “Making Art with Communities – a work guide,” 2007.

- Lina Srivastava, The tongue-tied storyteller in Rwanda: Lina Srivastava at TEDxTransmedia 2013, 2013.