A Critical Analysis of the Integrated Industry Waste Tyre Management Plan of South Africa

Volume 6, Issue 2, Page No 1046-1054, 2021

Author’s Name: Nhlanhla Nkosi1,a), Edison Muzenda1,2, Mohamed Belaid1, Corina Mateescu3

View Affiliations

1Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, 2117, South Africa

2Department of Chemical, Materials and Metallurgical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Technology, Botswana International University of Science and Technology, Palapye, 35101, Botswana

3Department of Civil and Chemical Engineering, Collage of Science, Engineering and Technology, University of South Africa, Florida Campus, 32004, South Africa

a)Author to whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: nkosinhlanhla1@gmail.com

Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 6(2), 1046-1054 (2021); ![]() DOI: 10.25046/aj0602119

DOI: 10.25046/aj0602119

Keywords: Achievements and failures, REDISA Plan, South Africa, Waste tyre management

Export Citations

Municipal general waste accumulation including the general waste category of end-of-life tyres has become a universal predicament especially in the majority of first world countries as well as in the third world countries. South Africa is recognized for its economic growth and improved living standards of people which has led to the increased accumulation rates of waste tyres. Consequently, the South African government declared its intentions to divert all categories of end-of-life tyres away from municipal dumping grounds as they present acute health and ecological threats. The government gazetted the Recycling and Economic Development Initiative of South Africa (REDISA) Integrated Industry Waste Tyre Management Plan (IIWTMP) in 2015 that seeks to manage and reprocess waste tyres bringing about environmental sustainability and economic prosperity through the simultaneous creation of jobs. This work, therefore, is a theoretical literature review study that highlights the achievements and failures of the Plan. Despite it being a comprehensively drafted and well-rationalized plan, REDISA drew negative public scrutiny from various stakeholders and institutions such as the Organization Undoing Tax Abuse (OUTA), Retail Motor Industry Organization (RMI) and television programs like Carte Blanche. The findings show that REDISA did manage to make significant contributions to the different sectors governing the Plan such as the creation of jobs and small, medium, and micro-sized enterprises (SMMEs), the establishment of depots and waste tyre processing facilities and, the investment into several institutions of higher learning to further research and development in the waste tyre sector. The plan ultimately ceased operation citing several unsound practices such as corporate administrative issues, deviating from the National Environmental Management (NEM) Amendment Law Bill, failing to carry out the duties outlined in the original Plan. Lastly, REDISA did not comply with operational and performance goals.

Received: 24 December 2020, Accepted: 02 February 2021, Published Online: 22 April 2021

1. Introduction

This article comes as a result of work previously presented on the REDISA Plan by [1, 2] and an extension of a paper originally presented in the Proceedings of the 7th International Renewable and Sustainable Energy Conference, IRSEC 2019 [3]. In this study, the capabilities of the REDISA Plan to deal with waste tyre management in South Africa are critically discussed. Consequently, this present paper serves to provide a follow-up and also reports on the successes and failures of the Plan.

The South African economy has in the past two decades experienced rapid growth, resulting in significant mass production of goods and services to realize the socio-economic demands of its rapidly increasing society [4]. This phenomenon has resulted in the increasing growth of municipal general waste earmarked for landfilling despite the unavailability of land. In 2011, an approximated quantity of 60 million scrap tyres was estimated to have been illegally dumped in open fields across the country, moreover, roughly 11 million waste tyres are supplemented annually into the accumulation figures [5]. In response to the waste tyre predicament, the South African Government endorsed the IIWTMP for REDISA in accordance with the NEM: Waste Act, 2008 as specified in the Government Gazette 35147 of 17 April 2012. The REDISA Plan showed promising prospects as it satisfied and acted in response to the fundamental requirements of the IIWTMP, for instance; the incorporation of the waste hierarchy; the inclusion of previously underprivileged societies; employment creation prospects particularly the previously economically excluded and the poor and its impartiality from national and local government structures. The Plan came into existence in 2013 for the sole purposes of reprocessing waste tyres in order to grow the waste tyre industry and create marketplaces for re-purposed tyre end-products; the establishment of viable green jobs as well as advancing SMMEs. Affirmatively, in 2017 approximately 221,751 tonnes of waste were generated with 64,061 tonnes (29%) being recycled/recovered and the remaining 157,690 were disposed of at landfill sites [6]. In 2019, the Waste Management Bureau (WMB) reported the generation of 170,266 tonnes of waste tyres of which approximately 77% was collected while 24% of the collected tyres were processed [7]. Also, promising waste plastic recycling rates were reported by Plastics SA in June 2018, 46.3% [8] of plastic products were recycled which is significantly above the recorded European recycling rate of 41.9 % for 2017 [9].

The South African Government is known for drafting excellent policies and regulations with little movement with regards to execution and implementation. It is our view and suggestion that the South African government should start focusing on putting mechanisms that progress the execution and implementation of policies and regulations.

Numerous programmes that seek to address the management challenges associated with municipal general waste accumulation have been proposed and adopted by different countries, One such program is the “Extended Producer Responsibility” (EPR) policy which South Africa has also adopted [10]. Other waste management programs include the: Tax Program, Free Market Program, Product Stewardship Program and Hellenic Program which were adopted by other countries. They are comprehensively discussed in section 2. The adoption of the EPR in South Africa has led to the development of the IIWTMP, which is intended at satisfying the tyre producer’s responsibilities for EOLT, through an obligatory EPR scheme [11].

2. Alternative Waste Tyre Management Programs

In July 2003, The European Union (EU) member states banned the landfill disposal of solid tyres [12] and subsequently; the landfilling of crushed tyres in July 2006 [12, 13]. This gave rise to the statutory framework to remedy the predicaments presented by waste tyres across EU member states. As a result , the EU developed several forms of waste tyre management models, namely the Tax Program; Free Market Program and the EPR Program that can be implemented to oversee the management, directing, and reclaiming of waste tyres in a systematic and ecologically friendly manner. Two additional programs, namely, the Product Stewardship Program and the Hellenic Program have been employed by other developed and developing countries. The most common models are reviewed in this section.

2.1. Tax Model

In this model, the state is responsible for the reclamation and reprocessing of waste tyres. This program is funded by a tariff imposed on the retail purchasing of new tyres by consumers. Denmark and the Slovak Republic are examples of states that have adopted this scheme [13, 14].

2.2. Liberal Market Model

The policymakers put in place the aims and objectives that this scheme will operate under; conversely, they do not delegate any duties to any individual body. All stakeholders within the production chain function under free-market specifications, however, must conform to policy regulations. States operating in this program are Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Germany, Ireland, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom [13, 14].

2.3. Extended Producer Responsibility Model

This program requires tyre manufacturers and distributors to take accountability for handling waste tyres as they have initially positioned them in the market. These parties are responsible for the establishment and management of initiatives that will ensure the recycling/recovery of waste tyres. The program is funded through a fare levied against the acquisition of new tyres. Similarly, with South Africa, 75% of EU States have employed the EPR Program [15]. This model has yielded positive outcomes and is realized to be financially and ecologically sustainable. In 2010, EU countries operating under this scheme reprocessed 44% of EU waste tyres generated and in 2011, the figure rose to 57% [13]. Likewise, with the REDISA Plan, records from EU member states show that substantial funds have been provisioned for research and development where capacity development and technological improvements on waste tyre reprocessing are being advanced. Over the years, the scheme in numerous EU states has recorded decreases in the collection of revenues and increases in the various ELT recovery schemes [13]. Reprocessed waste tyres were employed in various sectors, for instance; government-funded construction projects and civil works or as fuel replacement in cement production and power plants [13]. EU states such as Belgium, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Norway, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, and Sweden operate under the EPR Programme and some have managed to obtain 100% waste tyre recovery rates [14].

2.4. Product Stewardship Model

In Canada, the Product Stewardship Program is used in conjunction with the EPR Program to manage end-of-life tyres. Conversely, this Program appoints the recovery duties of waste tyres to provincial or local governments utilizing the levy imposed on tyre producers. The Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME), in 2017, pronounced its intentions to entirely adopt the EPR scheme [16]. The funds collected from Canada’s EPR Program aids in the gathering, shipping, and reprocessing of waste tyres [17]. Similarly, with EPR models of other states, a certain percentage of the finances is designated to research, the expansion of new products and to invest in further technological advancements [16]. Brazil and Korea have adopted the Product Stewardship Programme to oversee the management of their waste tyres. In Brazil, tyre distributors are obligated to manage 20% extra scrap tyres in addition to the quantities they import yearly, while in Korea manufacturers and distributors are reimbursed their funds subsequent to the collection of waste [15].

2.5. Hellenic Model

In July 2004, this Program was introduced by Greece to manage their waste tyres. In a nutshell, the Hellenic system incorporates all the other conventional systems in a single scheme [18]. It is evident in literature that in 2018, under the Hellenic model, Greece successfully collected a total of 49,783 tonnes of waste tyres of which 75.6 % was recovered and 15.8% was applied in energy recovery initiatives [19].

In the United States (US), the following bodies: customers, producers, recyclers, traders, states, and end-users shoulder the obligation to contributes towards the subsidy required to manage waste tyres [20]. The funds are utilized in the reclaiming, recycling or the material and energy recovery from waste tyres. Furthermore, a portion of the resources may be utilized to offer financial support to local communities for the establishment of waste tyre market initiatives, create licensing/enforcement systems, and to organize tyre educational programmes. National or local governments may also use the funds to provide grants or advances to waste tyre reclaimers and end-users of tyre-derived products [21]. The U.S. Tire Manufacturers Association in 2017 reported that 4.20 million tonnes of waste tyres were generated of which 3.40 million (81%) tons were designated for the market [22]. Conversely, 96.9% of scrap tyres were handled in an ecologically sound approach, 43% was designated for tyre-derived fuel in cement production and the paper industry; 25% was used as ground rubber; 8% was utilized for civil engineering purposes, and 3% was exported [22].

3. The Synopsis of The REDISA Plan

The minister of the Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA), in 2012 affirmed the South African Government’s objectives to ban the land disposal of all waste tyres varieties [23]. REDISA proposed an all-encompassing plan whereby an array of waste tyres would be redirected away from landfills for recycling and reprocessing. Previously excluded communities such as waste pickers were incorporated into the Plan to provide sustainable jobs and to prevent EOLT from being burnt in open fields or repurposed to be utilized in motor vehicles presenting possible threats. The various types of tyres that were incorporated in the REDISA Plan are shown in Table 1. The waste pickers took responsibility for the collection of waste tyres where they would at a later stage deliver them at designated collections depots across the country. The tyres are subsequently trucked and transported to processing facilities. A greater share of the tyres is grounded for use in the formation of road works and playing fields [6]. Several South African based companies, namely; Portland Pozzolana Cement (PPC), Lafarge, Afrisam, and Natal Portland Cement have realized the benefit of supplementing their cement kilns with waste tyres for their cement manufacturing processes, such as a 15% save in coal usage and fewer emissions of noxious gases [24]. Furthermore, Langkloof Brickworks, a brick manufacturing company based in Eastern Cape, is co-combusting coal and waste tyres, resulting in reduced CO2 emissions and energy consumption [25].

Table 1: REDISA tyre classifications [26].

| Tyre classifications | Type |

| 1 | Passenger |

| 2 | Light- duty industrial tyres |

| 3 | Heavy-duty industrial tyres |

| 4 | Earthmoving |

| 5 | Agricultural |

| 6 | Motorcycle |

| 7 | Industrial |

| 8 | Aircraft |

| 9 | Any other pneumatic |

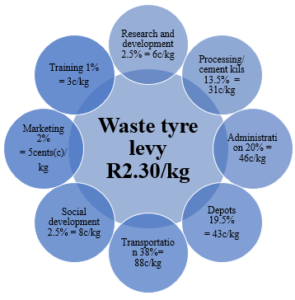

The imposed levy of (South African Rand) R2.30 per kilogram (1United States Dollar = 14.97 South African Rand) of each tyre sold was perceived to be the revenue utilized to fund the REDISA Plan, this was founded on the notion of “the polluter pays” [26]. To recuperate the expenditure of the waste tyre management process, REDISA imposed a levy on contributors considering the initial costs apportionments, shown in Figure 1. REDISA had previously proclaimed there will be minimal manipulation of the Plan by influential individuals [26]. However, the approval and implementation thereafter of a single waste tyre management Plan might be recognised as the weakness of the REDISA Plan. The monopoly created by the REDISA Plan resulted in challenges in the systemic implementation of the approved Plan and failures in reaching pre-planned targets. This eventually led to its collapse and insolvency.

In 2015, when the REDISA Plan was legislated, the organization was granted the freedom to treasure the waste tyre fee, where preferably it could have been channelled to the general fiscus [27]. This flaw in the Plan received criticism from many organisations such as the South Africa Tyre Manufacturing Conference, the Retail Motor Industry Organisation, and the Tyre Dealers Association. Consequently, these organisations instigated court applications arguing against REDISA’s dominance in the IIWTMP and the gathering of levies instead of assigning the responsibility to the South African Revenue Services (SARS) [27]. Despite the controversy associated with the acceptance of the REDISA Plan, the Plan was effected in 2015 using the half a billion Rands accumulated during its first year of inception. Presently, it is evident that the criticism argued by these organisations were justifiable and held merit. This led to REDISA experiencing lots of implementation challenges and ultimately its failure. In contrast to the REDISA Plan, the plastic bag waste management levy was launched in May 2003, where revenues of approximately R200 million were accumulated annually [28]. However, only 15%, equating to R30 million, of the collected funds were reserved for the DEA to directly contribute to the development of the plastics sector [28]. Likewise, the goals of the REDISA Plan and the plastic bag project were comparable in nature. The core objectives of the two initiatives were to further develop the waste collection value chain, create viable jobs, establish SMMEs, capacity development and skills advancement. However, the set targets did not materialize in both instances. The successes and failures of the plastic bag levy initiative are comprehensively reviewed by [28].

Figure 1: REDISA initial costs allocations [26].

4. REDISA Accomplishments

Statistics show that the South African recycling industry currently provides jobs for 100,000 individuals [29] and the waste recycling industry is recognized for its significant contribution to the country’s wealth, public health, welfare, and in environmental conservation [30]. Moreover, the waste recycling sector has the potency of making advancements in the waste to energy and material recovery fields. This denotes the capacity that the collection and utilization of waste may have in the creation of sustainable employment for the non-formal sector. This can be achieved through the collection of waste, the establishment of waste processing enterprises, the transportation of waste, the expansion of capacity within the waste sector, as well as research and development to advance the sector and its end products.

4.1. Micro collectors

Micro collectors play a pivotal role in the waste tyre management chain, as they are directly involved in the sourcing and collecting of waste tyres. The collection of waste tyres is perceived as a practice that has the potential to alleviate unemployment and poverty in disadvantaged communities. Micro collectors from, Soweto, Johannesburg have found a profitable opening from discarded tyres through the founding of a collaborative business enterprise [31]. Nevertheless, micro collectors still experience challenges like demeaned social value, substandard living, poor occupational conditions, and the scarcity of state funding.

4.2. Transporters

REDISA further saw an opportunity to create more sustainable jobs by contracting self-sufficient transporters for the shipping of waste tyres to storage depots and processing plants [31]. Waste collection and transportation, in this instance, provide livelihoods to many underprivileged communities and contributes to the establishment of micro-businesses.

4.3. SMMEs

The establishment of SMMEs was one of the key objectives of the REDISA Plan, this was realized with the founding of Dinotshi Waste Into Worth Project (Pty) Ltd., a waste tyre pre-processing depot in Midrand, Gauteng [32]. This was perceived as a noble initiative for the empowerment of underprivileged societies and the youth.

4.4. Research and Development

The authors in [27] and [28], reported that REDISA during their tenure sponsored 19 student bursary beneficiaries. Considering the large sums of funds that REDISA collected, the company could have done better by providing financial aid to students from various institutions in multiple disciplines and educational echelons. Sponsoring students at advanced graduate level could have aided in the research informed development of the waste tyre sector, creation of local expertise and ultimately contribute towards the benefit of REDISA and the South African economy.

5. REDISA Failures

In November 2012, the REDISA IIWTMP was accepted and contracted to oversee the collection, management, and processing of waste tyres for a term of 5 years, till 30 November 2017. In 2013, the DEA and numerous interested parties began questioning the execution of the REDISA Plan [33]. Consequently, in 2015, the DEA commenced examining the plan and subsequently an intermediary assessment was conducted during 2016.

5.1. Operational non-conformities

In reaction to proposals presented by various participants, the DEA initiated countrywide compliance and administration campaign at all the depots registered under REDISA in the country from the 25th to the 27th of November 2015.

One of the depots that were investigated was the Midrand Depot. The review team, appointed by the DEA, was privy to the Environmental Management Inspector (EMI)’s Report which cited several areas of concerns at the depot, such as; non-compliances with the Waste Tyre Regulations (WTR) of 2009; daily running of business activities while lacking the necessary Fire Registration Certificates and Occupational Health and Safety Certification; the non-existence of site-detailed waste tyre stockpile area plans (drawings and site-specific plans pertaining the management of the stockpiles at the numerous sites), and the authorisations thereof. Moreover, the depot neglected to deliver documentation/ records to the EMI to demonstrate conformity due to REDISA limiting the depot access to critical data, lastly, the depot manager lacked understanding of the REDISA IIWTMP and the necessities of the WTR,2009 [6]. Furthermore, the investigative journalism television program, Carte Blanche, compiled an exposé which aired in late 2015, where numerous disparagements were made against REDISA and the inadequate execution of its Plan. Consequently, the DEA instigated criminal indictments against the Midrand Depot founded upon the EMI’s findings on the substandard status of the depot [34]. Owing to the acute effect of fires posed by tyres, collectively with the effect they have on the environment, human health, and general safety concerns; the DEA has an obligation to act on non-conformities. Subsequently, the DEA released pre-compliance notices to the management of all depots operating under REDISA [34]. Table 2 shows the status of the reviewed depots as of 23 February 2017 and the improvements conducted by the WMB by May 2018.

In February 2016, a private consulting firm, iSolveit, was assigned by the DEA to carry out a performance review on REDISA. The findings of the review were later substantiated by Ernst and Young after REDISA refuted the outcomes of the report. The results and conclusions of the review report indicated the failure by REDISA to meet its implementation objectives, lack of proper management, nonconformities to the approved Plan, misuse of finances and non-compliance to the latest governing framework [34].

5.2. Organizational non-conformities

The major administrative issue presented was that three REDISA directors were found to also hold indirect shareholding in other businesses that are associates of REDISA, namely, Kusaga Taka Consulting (KTC) Proprietary Limited and the Product Testing Institute (PTI) [34-36]. This constituted opposing interests for all parties concerned, thus, presenting a digression from the initial Plan. This is an oversight in the part of REDISA; however, the overseeing government ministry should also shoulder the responsibility for its lack of monitoring and assessment. The DEA conceded in court documents that it became aware of this relationship in May 2016 and failed to act promptly [35]. After endorsing a single waste tyre management plan, constant monitoring, and administration of REDISA were required from the part of the DEA.

Furthermore, allegations of excessive remuneration packages were levelled against non-managing directors of REDISA that were discovered to earn over R1.92 million annually, apart from extra company benefits. The collective earnings of managing directors and staff of REDISA (roughly 7 individuals) were reported to be R20.40 million per annum in totality [34]. A parallel evaluation on non-profit organisations shows that a Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of a non-commercial entity earns typically a salary of R469,587.00 yearly [34], however, the REDISA CEO was found to earn an exorbitant remuneration of R4,164, 840.00 per annum [35]. This scenario at REDISA only perpetuated the inequalities that already exist in South Africa by increasing the income disproportion between the impoverished and the wealthy.

The Plan instructs for the employment of an external administrative company that will manage and implement the mandates of the REDISA Plan and the management body is to report annually to the DEA on all matters pertaining to the Plan as stated in section 28 of the REDISA IIWTMP [26]. REDISA’s memorandum of incorporation (MOI) also makes provision for this clause [35]. However, since the commencement of the Plan, all reports were presented by REDISA to the DEA [34]. This is a divergence from the governing framework detailed in the Plan. There seem to be evident associations between REDISA NPC and KTC (the administrative firm employed by REDISA). Consequently, this would directly influence on monitoring and assessment as well as performance management of the different organizations, in this lies the administrative error [34], [37]. REDISA was also found not to have a suitable record-documentation system [34]. There were also concerns regarding meeting resolutions and their legitimacy or lawfulness [37]. Additionally, REDISA’s monetary books of the year ended 29 February 2016 indicate substantial capital financing into the PTI of R61,852,000.00 [34], [37]. Yet, the department could not categorically determine how the investment advances the benefits of REDISA and its mandate. Lastly, it was reported that some of the family members of REDISA directors were also the directors in a privately-owned company, namely Nine Years Investment (Pty) Ltd (NYI), that leased office space to REDISA, moreover, NYI possesses 75% shareholding in KTC [35], [37].

On the 24th of January 2019, the Supreme Court of Appeal acquitted REDISA of all liquidation charges brought against the company in 2017 at the request of the then environmental affairs minister. However, one of the proceeding judges strongly criticized her colleagues for completely discounting the proven exorbitant salaries of REDISA executives.

5.3. Performance nonconformities

Employment creation: One of the key objectives of REDISA was the creation of employment particularly for the destitute, previously disadvantaged, and small enterprises through the collection and distribution of tyres to the 150 REDISA depots situated countrywide [26]. As mandated in the REDISA Plan, the organization was liable for the identification of micro-collectors, providing the necessary training and development, the creation of business opportunities and the awarding of specific collection points. Ultimately, this will ensure that the operator will have the needed skills to own and successfully operate and manage the depots. Table 3 shows REDISA’s records of achieved job targets; the organization only created 1435 jobs instead of the projected 2860 jobs at the close of year 4. As a result, REDISA accomplished 50 % of its job creation objective for the year ending 2016.

Skills training and development: Section 25 of the Plan, states that free training of individuals for basic skills and specialized proficiencies in the waste tyre industry value chain should be provided. This is inclusive of drivers, their crews as well as accounting and management staff [26] utilizing 1% of the received earnings earmarked for training and development. Thereafter, the attendance reports were to be documented in the National Centralised Computer Systems (NCCS) [26]. However, REDISA failed to provide records for this. For the financial year ending 29 February 2016, the organization collected R432,372,000.00 from the waste tyre levy and 1 % of this amount, equating to R4,323,720.00 was supposed to be spent on training and development [34]. However, their financial records show that

Table 2: REDISA tyre classifications [26].

| No | REDISA depot | Non-compliance notices | Non-Compliance noted | Improvements conducted by WMB as of May 2018 |

| 1 | Polokwane Depot, Plot 10, Geluk, Dalmada, Limpopo | 09/12/2016 | Outstanding registration with the Limpopo Provincial Department,

Fire and safety compliance certificate outstanding, Storage layout plan not approved. |

Registration forms submitted.

Storage layout plan submitted to the Municipality. |

| 2 | Waltloo Depot, Pretoria East, Gauteng | 07/11/2016 | Fire and safety clearance certificates renewal,

Records of compliance checklist outstanding, Storage layout plan not approved. |

Fire certificate renewed,

Inspections conducted by safety, health and environmental (SHE) representative, Storage layout plan endorsed by Fire Chief. |

| 3 | Silverton Depot, 309 Derdepoort Road, Silverton, Gauteng | 18/12/2015 | Site closed on 15/08/2016. | Site closed on 15/08/2016. |

| 4 | Midrand Depot, Boxer Road, Midrand, Gauteng | 28/10/2016 | No registration with Gauteng Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (GDARD) as a storage facility,

Waste not removed from 2016. |

Registration form submitted.

Waste not yet removed. |

| 5 | Thembisa Depot, Midrand, Gauteng | 28/10/2016 | No stormwater management onsite,

No registration with GDARD as a storage facility. |

Registration form submitted |

| 6 | Springs Bailing, Depot,

Springs, Gauteng |

24/10/2016 | Site closed.

|

Site closed.

|

| 8 | Westonaria Depot, Gauteng | Poor stormwater management. | Stormwater issue not addressed.

WMB in the process of closing site |

|

| 9 | Witbank Depot, Emalahleni, Mpumalanga (MP) | 02/12/2016 | None | None |

| 10 | Nelspruit Depot, Industrial Park, MP | 04/11/2016 | Waste tyre storage not approved,

Signage for operating hours and contact details not displayed at the main entrance, Site regulations not displayed at the entrance of the operational facility, Proof of fire prevention training outstanding for the security attendant, Waste tyre storage area haphazardly used with no demarcation lines, Storage area congested, No records availed to confirm stormwater management provision, Waste tyre storage not cleared of vegetation. |

Approval of storage layout plan is in progress,

Fire Chief scheduled to visit site on 11 May 2018, Signage has been installed, Training for security not undertaken yet, Tyres stored in compliance with WTR, 2009 with visible demarcation lines, Stormwater management not fixed yet, The vegetation is cleared regularly.

|

| 11 | Tlabane Depot, Moraka, Rustenburg, North West | 02/12/2016 | No fire breaks maintained from the perimeter fence,

Entrance signage does not display operating hours. |

Site still congested and the fire breaks along the perimeter fence,

Signage not updated |

| 12 | Bloemfontein Depot, Bloemfontein, Free State (FS) | 28/10/2016 | Poor stormwater management | Stormwater issue not addressed,

WMB closed site in May 2018 |

| 13 | Bloemfontein Depot, FS | Tyres not stored according to the WTR | Depot no longer operational | |

| 14 | Ladysmith Depot, Ladysmith | 04/11/2016 | No stormwater management on site | Stormwater management issue not addressed |

| 15 | Pietermaritzburg Depot, KwaZulu Natal (KZN) | 28/10/2016 | Site closed | Site closed |

| 16 | Cato Ridge Depot, Durban, KZN | No stormwater management on site | Stormwater management issue not addressed | |

| 17 | Clairwaste, Durban, KZN | 24/10/2016 | No stormwater management on-site,

Site not registered with the KZN Department of Agriculture and Environmental Affairs (DAEA). |

Stormwater management issue not addressed,

Registration form submitted. |

| 18 | East London Depot, East London, Eastern Cape (EC) | 04/11/2016 | None noted – New site | None noted – New site |

| 19 | Arlington (Port Elizabeth) Depot, EC | 24/10/2016 | No stormwater management on-site,

No Waste Tyre Storage Plan, No fire breaks in storage area. |

Stormwater channels developed and maintained,

Storage layout plan in place, Fire breaks established. |

| 20 | Atlantis Depot, Western Cape (WC) | No Fire and Safety certificate,

REDISA approved storage plan does not correspond to the current storage plan, 14 tyre piles exceeded the height of 3m, and 3 piles exceeded the prescribed length, 4 firebreaks were less than the prescribed 5m in the WTRs, No stormwater management on-site, Edges of the piles were outside the prescribed 8 meters fence perimeter, Site not cleared of vegetation. |

The plan has been submitted to the local authorities and the Fire Chief has responded with recommendations to be implemented,

Depot capacity is continually monitored, and tyres being placed in designated area.

|

|

| 21 | Mossel Bay Depot, Mossel Bay, WC | 07/11/2016 | Piles more than 3 meters in height,

Piles also stacked outside the perimeter of the site. |

Site is compliant with its storage plan. |

Table 3: Projected rates of employment creation [26].

| Department | Commencement | First-year projection | Second-year projections | Third-year projections | Fourth-year projections | Fifth-year projections | Final projections | ||||||

| Magnification | Sum | Magnification | Sum | Magnification | Sum | Magnification | Sum | Magnification | Sum | Magnification | Sum | ||

| Head office | 200 | 1 | 200 | 1 | 200 | ||||||||

| Depots | 12 | 3 | 36 | 27 | 324 | 40 | 480 | 40 | 480 | 40 | 480 | 150 | 1800 |

| Recycling | 20 | 2 | 40 | 8 | 160 | 12 | 240 | 14 | 280 | 14 | 280 | 50 | 1000 |

| Transportation | 1.75 | 300 | 525 | 600 | 1050 | 800 | 1400 | 1200 | 2100 | 1100 | 1925 | 4000 | 7000 |

| Total jobs | 801 | 2120 | 2860 | 2685 | 10 000 | ||||||||

only R779,000.00, 18% of the target, was utilized on training [34].

The advancement of SMMEs: REDISA outlined that managers of depots can in the long run after acquiring the necessary skills and competencies to become fully independent and occupy ownership of the depots, as stated in section 2.1 in the Plan [26]. REDISA failed to report on the statuses, and growth magnitude of all SMMEs contracted under REDISA. Furthermore, with the recent Covid-19 pandemic affecting global markets, including the South African economy, the SMME sector has also been severely affected. This is phenomenon is expected to further reduce the already diminished number of successful small businesses in South Africa.

Table 4: REDISA targets and actual performance figures [38].

| Target | Estimated 5 Year Target | Actual performance figures as of year 4 |

| Jobs | 10 000 | 1435 employment opportunities created by REDISA – 50% of the projected target. |

| Depots | 150 | 25 depots of the projected 110 – 23% of the target |

| Processors | 50 | 21 processors of the estimated 36 – 58% of the target |

| Transporters | 4000 | 121 transporters of the estimated 2900 – 4 % of the target |

| Training | 1% of revenue | 18% of the training budget was utilized. |

| Research and Development | 2,5 of revenue | 0,26% of the research budget was utilized. |

Research and development: Section 25 of the Plan makes provision for research and development and this was included in the organization’s deliverables. The cost allocation for research and development was 2.5% of the earnings received. Also, this revenue stream was to be inclusive of funding research and development at institutions of higher learning. It is well documented that REDISA partnered with Stellenbosch University and gave attention to the advancement of technologies for the valorisation of scrap tyres, with the core focus of establishing novel commercial opportunities and ventures. On record, REDISA subsidized a mere 2 out of 26 tertiary institutions in the country [34], the organization could have supported more tertiary institutions and thus expanding on their waste tyre technology research. The monies spent on research and development as recorded in December 2015 in the company accounts was R1.14 million, suggesting that only 0.26% of the research funds we utilized which is far less than the 2.5% allocation as part of the Plan [34].

Table 4 assesses the goals set by REDISA ahead of the approval and execution of the Plan with the actual attained performance figures. It is evident from Table 4 that REDISA managed to make significant contributions to the different sectors under their Plan, but it did not attempt to meet any of its set objectives.

5.4. Deviances from the REDISA Plan

The exportation of tyres: In section 12 of the Plan, a provision for the exporting of tyre derived goods is made, however, the export of waste tyres is not catered for. Moreover, the Plan pronounces that modifications to the Plan can only be accepted by the DEA minister [26], [34], [36]. The report submitted by REDISA on 31 October 2016 details the percentage quantity of waste tyres that were exported. Roughly 30% of the monthly received tonnages were exported whilst the remaining tonnages featured minimally in the tyre recycling processes and rarely recorded in the monthly processing statistics [34].

Compensation of collectors: The findings from iSolveit Consulting in 2017 show that waste collectors were compensated a standard rate of R2.00 per tyre [34], [38], conflicting with the rand per kilogram rate stipulated in the Plan. The Plan suggests that the informalized economy (waste pickers) handles the greatest share of waste tyre projected to be roughly 75% [34]. In July 2016, REDISA provided a list of all the waste collectors captured in their database. A total of 965 pickers were enlisted, of which only 8.7% of the total were gathering tyres. Of the remaining 881 pickers, 53.1% were registered in the database but failed to gain position of their identification cards, whereas 39.2% had received their cards but did not manage to supply tyres [34]. On average, the yearly earnings of the 512 waste pickers varies between R463.14 to R14,935.55 during the 2016/2017 financial year. An additional 370 waste collectors had R1,681.55 distributed to them [34]. Consequently, REDISA retained monies for 881 waste pickers which were designated for salaries, registration, and training. A comparison study was conducted to assess the earnings of approximately 7 REDISA executive management against those of waste collector (965 individuals), generally, R20,40 million and R280,036.00 respectively were the averages remunerated to the different groups in the 2016/17 fiscal year. The earnings paid to the informal waste collectors only equates to 1.37% when compared to the remuneration of REDISA executives. This indicates that REDISA was unsuccessful in the creation of sustainable employment, consequently, did not meet the performance targets as stated in the Plan, and failed in lessening the income inequity between management and labourers.

Compensation of transporters: Section 25 of the Plan specifies that primary and secondary tyre transporters should be remunerated per kilometre travelled [26]. However, contracted transporters were reimbursed a standard rate per route not as initially stipulated in the Plan [34], [38].

Additional waste stream: In December 2015, the REDISA management accounts reflected an R11 million investment in the investigation of a new waste stream, however, this is not within the prescript of the Plan [34], [38]. This decision is perceived to be financially unsound as this venture does not institute additional revenues.

Table 5 summarizes all the non-conformity concerns established during the implementation of the REDISA IIWTMP.

Regardless of the criticism and shortcomings of the implementation of the REDISA Plan, in principle, the plan was sound and showed great potential if implemented in the approved manner. At current, the WMB has been assigned the responsibility to oversee the collection, storage, transportation, and processing of waste tyres in South Africa. Table 6 shows the statistics of active participants of the WMB as of June 2018. In May 2018, the then minister of the DEA gazetted the receipt of four new proposals for the Industry Waste Tyre Management Plans in South Africa, namely, Tyre Waste Abatement & Minimisation Initiative of South Africa, Evergreen Energy, JPC Energy Systems and South African Tyre Reuse Company [39]. However, the current Minister of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries, on 19 September 2019, issued a notice of rejection for all the previously submitted IIWMPs and found them unsuitable to address the waste tyre challenges in South Africa [40]. The Minister later issued a directive for the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) to draft an industry waste management plan for waste tyres [9].

Table 5: The abstract of REDISA’s performance assessment [38].

| Administrative

errors |

Performance | Deviations | Alignment |

| Contradictory interests (executives at KTC, NYI and linked companies associated with REDISA). | Job performance figures below estimated targets. Only 50% achieved by Year 4. | 56% of waste tyres were exported, this was done against the approved Plan | REDISA was not affiliated with the new governing framework. |

| Board of Directors structure did not conform to the requirements in Plan. | NCCS was bought using REDISA funds, but KTC owned and managed the system and was also outdated. | Employment targets were revised. | |

| Functions and duties between REDISA and KTC not distinctively outlined. | Training targets not achieved – only 18% of training budget used. | R 150 million investment was provided to the Product Testing Institute | |

| Insufficient archiving of records (Board minutes, resolutions). | Employment targets for depots, processors and transporters not accomplished | Investments and investigations into an additional waste stream were embarked upon. | |

| Business did not conform to MOI-suitability of directors. | Excessively spent on marketing by 0,96%. | Waste collectors were remunerated a standard rate of R2,00 per tyre. | |

| Only 0,26% of research and development revenue was spent. | Transporters were remunerated a standard rate per route in a place of a per kilogram charge. | ||

| Yearly performance audits were never presented to the DEA |

Table 6: Waste Bureau Management performance figures as of June 2018 [41].

| Target | Active participants | |

| Micro collectors | 213 | |

| Transporters | 77 | Primary = 67 |

| Secondary = 10 | ||

| Micro depots | 23 | |

| Processors | 21 | Registered = 12 |

| Active = 9 | ||

6. Conclusion

The approval of the IIWTMP REDISA Plan was recognized as a progressive scheme from the South African Government that envisaged the integration of previously underprivileged societies, the establishment of tenable green jobs, a capacity-development project, and the commitment to deal with social and economic issues. The findings show that REDISA did manage to make significant contributions to the different sectors governing the Plan such as the creation of jobs and small, medium, and micro-sized enterprises (SMMEs), the establishment of depots and waste tyre processing facilities, and the investment into several institutions of higher learning to further research and development in the waste tyre sector. However, with REDISA not meeting its planned targets, non-conformities to functional and administrative commitments; monetary challenges as well the non-compliances of the initial Plan, REDISA saw its demise. The experiences realized with the REDISA Plan should give guidance to present and future policy and decision-making on waste tyre management and processing in South Africa.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the National Research Foundation (NRF), the University of Johannesburg’s Global Excellence and Stature scholarship for financial support. The authors also acknowledge the University of Johannesburg, the Botswana International University of Science and Technology and the University of South Africa for supporting this work.

- N. Nkosi, E. Muzenda, J. Zvimba, “An analysis of the waste tyre management plans in South Africa,” in 2013 ICIET International Conference on Innovations in Engineering and Technology, 104–110, 2013, doi:.doi.org/10.15242/IIE.E1213645.

- N. Nkosi, Waste tyre management trends and batch pyrolysis studies in Gauteng, South Africa, University of Johannesburg, 2014.

- N. Nkosi, E. Muzenda, M. Belaid, C. Mateescu, P. Bilal, “A Review of the Recycling and Economic Development Initiative of South Africa (REDISA) Waste Tyre Management Plan: Successes and Failure,” in 2019 IRSEC 7th International Renewable and Sustainable Energy Conference, 1–8, 2019, doi:doi.org/10.1109/IRSEC48032.2019.9078291.

- World Bank, South Africa Economic Update: Jobs and Inequality, Washington D.C, United States of America, Oct. 2020.

- L. Godfrey, S. Oelofse, “Historical review of waste management and recycling in South Africa,” Resources, 6(4), 1–11, 2017, doi:10.3390/resources6040057.

- Parliament of the republic of South Africa, Targets for diverting waste tyres from landfill sites, Cape Town, South Africa, 2018.

- Recycling waste tyres in South Africa, Innovation for Sustainable Development Network, 2019.

- Department of Environmental Affairs, South Africa State of Waste Report, 2018.

- S. Oelofse, Industry Waste Management Plan for Tyres, Pretoria, South Africa, 2020.

- Plastics SA Admin, Plastic recycling: South Africa versus Europe – Plastics SA, Industry News, 2019.

- D. Schmidt, Recycling of plastic packaging waste in the EU 2006-2017, Statista, 2019.

- M. Sienkiewicz, J. Kucinska-Lipka, H. Janik, A. Balas, “Progress in used tyres management in the European Union: A review,” Waste Management, 32(10), 1742–1751, 2012, doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2012.05.010.

- Etrma, End of life tyres- a valuable resource with growing potential, Brussels, 2011.

- M.R. Sebola, P.T. Mativenga, J. Pretorius, “A Benchmark Study of Waste Tyre Recycling in South Africa to European Union Practice,” Procedia CIRP, 69, 950–955, 2018, doi:10.1016/j.procir.2017.11.137.

- A.I. Felix, O.O. Ajayi, F.A. Oyawale, S.A. Akinlabi, “Sustainable end-of-life tyre (EOLT) management for developing countries – A review,” in 2018 ICIEOM International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations ManagementInternational Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, 1054–1064, 2018.

- Government of Canada, Overview of Extended Producer Responsibility in Canada, 2017.

- Government of Canada, Introduction to Extended Producer Responsibility, 2017.

- A. Karagiannidis, T. Kasampalis, “Resource recovery from end-of-life tyres in Greece: A field survey, state-of-art and trends,” Waste Management and Research, 28(6), 520–532, 2010, doi:10.1177/0734242X09341073.

- The Hellenic Recycling Organization, Recycling in Greece according to the data year 2018, Athens, Greece, 2018.

- J. Sheerin, Scrap Tire Management in the United States, 1–44, 2014.

- USA Environmental Protection Agency, State Scrap Tire Programs A Quick Reference Guide: 1999 Update, Washington DC, USA, 1999.

- Global Recycling, Tire Recycling Riding On, Oct. 2020.

- P. Mpyane, “What happens to all used tyres in our country,” Business Day, 2019.

- Next level, City Press, 2015.

- Promethium Carbon, Sustainability: 2017 Sustainability Report for the Clay Brick Association of South Africa, 2017.

- Department of Environmental Affairs, Act No 59 of 2008: National Environmental Management: Waste Act: Notice of Approval of an Integrated Industry Waste Tyre Management Plan for the Recycling and Economic Development Initiative of South Africa (REDISA), 2011.

- Y. Groenewald, “Tyre wars: Was tyre recycling scheme a money making racket?,” Fin 24, 2017.

- H. Erdmann, To ring fence or not to ring fence, Bizcommunityommunity, 2016.

- J. Viljoen, D. Blaauw, C. Schenck, “The opportunities and value-adding activities of buy-back centres in South Africa’s recycling industry: A value chain analysis,” Local Economy, 34(3), 294–315, 2019, doi:10.1177/0269094219851491.

- S. Kings, “Tyre recycling scheme hits the skids,” Mail and Guardian, 2017.

- Meet some of the women who have found the opportunity in waste tyre industry, R. News, 2016.

- Envirolution.co., Midrand Waste Tyre Pre-Processing Depot, SAHRA, 2017.

- Department of Environment Forestry and Fisheries, REDISA liquidation; Waste Tyre Plan; Waste Bureau: briefing with Minister, Parliamentary Monitoring Group, 2017.

- ISolveit Consulting, Key Findings Emanating from the Performance Review of Redisa NPC-Final report, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2017.

- A. Cachali, H. Saldulker, C. Van der Merwe, M. Molemela, O. Rogers, The Supreme Court of Appeal of South Africa Judgment, (January), 1–39, 2019.

- Department: Environmental Affairs, Portfolio Committee of Environmental Affairs presentation Presentation, 1–31, 2018.

- Enforcement Action, Detailed Summary of Verification of ISOLVEIT Findings – Annexure C, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2017.

- Department of Environmental Affairs, REDISA – Litigation, Performance & Deviations, 2018.

- Department of Environmental Affairs, Consulation of the proposed industry Waste Tyre Management Plans: Government Gazette 41612, Cape Town, South Africa, 2018.

- Department of Environmental Affairs, Completion of Consideration of Section28(1) Industry Waste Tyre Management Plans Submitted to the Minister for Approval, Pretoria, South Africa, 2019.

- Department: Environmental Affairs, Consultations on Proposed Waste Tyre Plans, (June), 1–174, 2018.