Touristic’s Destination Brand Image: Proposition of a Measurement Scale for Rabat City (Morocco)

Volume 5, Issue 6, Page No 1750-1758, 2020

Author’s Name: Abdellatif Elouali1,a), Smail Hafidi Alaoui1, Noura Ettahir2, Abderrazzak Khohmimidi1, Nadia Motii1, Keltoum Rahali3, Mustapha Kouzer3

View Affiliations

1Management Sciences Research Team, Faculty of Law, Economics and Social Sciences (FSJES) Agdal, Mohammed V University in Rabat, 10090, Morocco

2Management Sciences Research Team, High School of Technology Salé, Mohammed V University in Rabat, 10090, Morocco

3Laboratory of Agrophysiologie, Biotechnology, Environment and Quality, Faculty of Science, Ibn Tofail University, Kénitra, 14000, Morocco

a)Author to whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: abdellatif.elouali@gmail.com

Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 5(6), 1750-1758 (2020); ![]() DOI: 10.25046/aj0506209

DOI: 10.25046/aj0506209

Keywords: Brand Image, Touristic destination, Measurement scale, Morocco

Export Citations

The objective of this article is to highlight the existing relationship between the tourist’s destination brand image of the city of Rabat (Morocco) and its choice by foreign tourists to be visited once again. We suggest a reliable measurement scale able to measure the dimensions and associations of the brand image most memorized by tourists, so as to further attract the researchers and stakeholders curiosity in the tourism sector which face, every day, new challenges of attractiveness and sustainability of tourist destinations in the new Moroccan regionalization context. The survey is carried out on a sample of 454 foreign tourists in the city of Rabat because of the importance that this city requires in terms of overnight stays, that is to say nearly one million in 2018 according to the statistics of the Moroccan Tourism Observatory. The results obtained from the survey show that the functional and abstract associations jointly constitute the brand image of the city of Rabat in the foreign tourist’s memory and that the abstract associations are more significant in the destination’s choice.

Received: 14 October 2020, Accepted: 21 December 2020, Published Online: 30 December 2020

1. Introduction

Today, tourism in all its forms is marked by strong competition between tourist destinations at national and international levels. The emergence of a large number of tourist destinations has compelled tourism managers to adopt new managerial approaches [1]. Faced with this situation, it is no longer easy to attract so many tourists because these people are more demanding and seek quality or even total satisfaction regarding a precise destination. Henceforth, in order to market their tourist sites, tourism professionals will have an interest in mastering territorial marketing in order to position themselves clearly on the most buoyant markets by adopting strategies with a political brand trend [2].

Indeed, likewise several destinations, Morocco is positioned as a country with a purely tourist vocation with 13 million non-resident tourists in 2019, according to the Moroccan Tourism Observatory, this is because of the country’s geographical position, its natural and human resources, and its civilizational and historical heritage. Nevertheless, Morocco has been facing a fierce competition over the last decade with the emergence of countries such as Turkey with 39 million foreign tourists in 2018, Egypt with more than 8 million foreign tourists in 2017 and Tunisia with more than 8 million foreign tourists in 2018 (the Moroccan Tourism Observatory).

This is why our study focused on the study of the brand image of the tourist destination with the aim to analyze the measurement scale of the variable of the brand image of Rabat city tourist destination in order to define the different dimensions linked to it regarding the functional and abstract brand image. Consequently, we will present the concept of the Brand Image of the Tourist Destination and the multiple measurement instruments related to this concept in order to answer the following central questions: By which forms of perceived images can the attractiveness of Rabat city tourist destination be improved? And what are the associations with the brand image that have a greater impact on the choice of destination by tourists?

2. Territorial marketing: theoretical foundations

Territorial marketing research has experienced unprecedented growth over the last ten years. What all this research has in common is the application of marketing principles to the sphere, the territory, the city, and the destination [2]. In fact, several designations exist for territorial marketing: city marketing or public service marketing, urban marketing.

Territorial marketing does not only include communication strategies to promote the territory, but all the strategies that allow the attraction of tourists in relation to other territories. Territorial marketing is therefore based on effective, coherent and well-thought-out communication. The territorial brand plays a crucial role in this communication approach. From this point of view, the territorial brand is a means to attract not only tourists, but also investors, businesses and residents, who are also involved in the process of tourism development of a territory [3].

Although it is different from the enterprise, the territory will gain in adopting the strategies of the enterprise, especially the marketing strategy to be able to attract tourists in a context of strong competition [4].

3. The brand image: a multidimensional concept

The brand represents an intangible asset in order to attract new customers and subsequently building customer loyalty [1]. The brand fills numerous functions designed to support consumption. In this way, the brand carries a value and brings certain notoriety [5]. The brand is a product communication tool. For the consumer, the brand confers a reference point with which he can identify [6]. It makes it possible to identify and make the city desirable in the eyes of visitors [7]. At the level of a tourist destination, the brand takes the form of a name and a logo. For the destination, the brand carries its identity and protects its reputation [1]. The territorial brand is used as a lever of attractiveness of a tourist territory, within the framework of territorial marketing [8].

In [9], the author explains that the mark is both a signifier and a signified. It is a signifier because it enables the goods to be distinguished. Distinction does not only derive from sight, but also from other senses: touch, hearing, taste, smell. But as a signifier, the trade mark evokes a sense in the consumer. In [10], the author reports the characteristics of a brand at the territorial level, arguing that the territorial brand refers to the perception of the reputation of the territory by internal and external actors. The territorial brand therefore aims to convey the meaning of the city object. Furthermore, the city itself has always been considered a mark by nature, inasmuch as its name enables it to distinguish itself from others. Moreover, the name of a city already evokes its reputation and image in the mind. The territorial brand therefore encompasses all perceptions relating to a place and its inhabitants [11].

3.1. The notion of brand versus the notion of brand image

A differentiation is to be made between the brand and the brand image. The latter corresponds to the mental image that emerges in the individual when he hears, sees or evokes the brand [12]. In [13], the author explains that brand image corresponds to “all the associations and impressions that a consumer has in his memory about a brand. In other words, the brand image designates everything that comes to mind when talking about a brand. It can be tangible elements such as the goods or services bearing the brand, but it is also possible to associate the brand image with abstract elements from the producer’s communication or from other competing brands [14]. As a result, the brand image could be assimilated to consumer representations or perceptions of a brand. It has emotional, rational and memory dimensions. However, for the consumer to be able to remember an attribute of the trade mark, he must have already experienced it or at least have been exposed to it on many occasions. The brand image is therefore the result of experiences resulting from the use of the product or exposure to it [15].

Within an enterprise context, the brand image is the perception of the brand by all stakeholders and the public [16]. From the marketing point of view, the touristic territory is assimilated to a product for sale and is associated with the brand. The territory becomes a brand that has its own image to promote through branding, but the brand image could also be considered as the characteristics that allow the individual to evaluate the brand in relation to others. The characteristics taken into account are in most cases concrete attributes [17].

The brand image of a tourist destination corresponds to its mental representation by the consumer. From this point of view, symbolic meanings are associated with the characteristics of the destination in question. This representation varies according to the experience or communications made by marketers and/or acquaintances who have previously experienced the tourist destination [18].

3.2. Brand image psychological approach

The branding process formation is split into four phases [19]: The first phase acts to express the process of the image perception by the individual’s senses. It is primarily the physical characteristics of the product and the consumers’ expectations and interests that affect or not the consumers’ attention. If the consumer doesn’t grasp the stimulus of the product by the senses, then the perception is not possible and ultimately the purchase will not occur.

During the second phase the consumer decodes the stimulus and interprets it according to his learning. This phase is unique to each individual.

The third phase deals with the perception’s mental representation. The perceived image embodies a meaning and is somehow translated.

It is at the fourth phase that the individual can, through his evocation capacity, make a judgment, express an opinion, feel about the perception or simply take to purchase decision. The image itself can be divided into a desired image, transmitted image and perceived image [20].

3.3. Related associations to the brand image

In order for a brand to trigger a consumer’s positive attitude, the consumer must develop strong and positive associations with the brand. It is therefore essential to create a strong image [14]. The structure of an image depends on the key attributes of the tourism product as well as the associations with the brand. However, the attributes and associations to the brand are derived from the different information retained in the consumer’s mind after a consumption experience. Interactions at tourist destinations structure a complex image of the destination. The associations derive from this fact, from the confrontation between the image of the destination as perceived by the visitor before the experience, and the one developed after the tourism experience. Moreover, this complex image corresponds to the brand image perceived by visitors [21].

Branding consists of associations linking the individual to a brand. These associations can be functional or abstract. Functional associations group together attributes situations of use, benefits of using the product. Abstract associations, on the other hand, involve psychological phenomena such as affects, the attribution of a symbol to the trade mark or the emotions that the individual experiences in relation to the trade mark [18].

The functional or symbolic association with the image depends on the intensity and frequency of the positive experiences that the consumer has with the product [6].

4. Perception of destination’s brand image as a communication strategy

The strong growth of the tourism industry has prompted many destinations to position themselves on this market [22], not only capital cities (Paris, London, Vienna, …) but also cities that have developed a scientific (Cambridge) or cultural (New York, Aix-en-Provence, Dijon, …) image, art cities such as Venice or emerging cities that have developed their own identity (Prague, Istanbul, Seville) [23].

Indeed, the competition between territories and even between cities has triggered the rise to an action mode which assumes the rise of reflections on attractiveness at several levels. Territories and destinations are the first willing to produce discourses to attract but also to retain a certain category of investors, tourists or residents.

In present day, the challenge for tourist destinations consists in differentiating themselves by developing a specific identity. They will carry out communication campaigns which may be reinforced by heritage images (culture, local customs, festivals, architecture, nature, etc.) intended to stage and perpetuate local traditions and culture [24].

Tourism communication therefore plays a capital role in the construction of the touristic destination image. Nevertheless, the multiplication of communication campaigns by the different territorial strata and the media coverage of the various events can blur the image of destinations.

Besides, it is important to study the effectiveness of communication between various territorial entities towards an urban destination in the light of the theory of social representations. Indeed, the development of destinations brands becomes compulsory for the cities’ survival in the face of international competition. In order to differentiate themselves, they must develop their own identity brand and consequently create a good image.

Let us point out that touristic destinations are no longer perceived as mere entry points, boarding locations or transit points during a trip, but also, they are seen as eye-catching sites (natural or cultural resources) and attractions (appropriate development for tourism of these resources) [25] of fully-comprehensive destinations.

Previously, destinations promoted themselves thinking that the creation of tourist attractions would suffice to attract tourists (European Travel Commission). Nevertheless, exposed to tourism development, to the multiplication of communication campaigns at the different territorial levels (national, regional and city), as well as to the media coverage of the various events (terrorist attacks, strikes; riots in some countries; Pandemic, for example (Covid-19), the images and representations of destinations may be blurred.

In other words, the image keeps a very important place in the choice of a destination, and the different information sources play a crucial role in the tourists’ minds regarding this image formation [26]-[28]. Consequently, the communication issued by destinations and touristic organizations influences the determination of the traveler’s attitudes and behavior as well as in the formation of the tourist’s image of a destination [29].

Typically, researches related to tourist destinations deal with the destination’s image, which is an essential element in the choice of a touristic destination [27], as it provides information on the specific and unique attributes related to the destination before the potential stay [28].

As a result, the destination’s image can, through its communication with tourists, generate a strong and distinctive image compared to its competitors. Moreover, many studies distinguish two types of images resulting from this formation process: the induced image resulting from the information of tourism actors (advertising and promotion of the destination and tourism organizations) and the organic image resulting from the consumers exposure to non-tourist information sources, such as the media outside the tourism sector [27], [28].

The organic image is often rooted in the tourists’ minds because it is made up of shared representations which convey stereotypes [30].

5. Measurement scales of the Brand Image of the tourist destination

The measurement of brand image is based on the associations that consumers attribute to the brand. The stronger are the associations, the stronger is the brand equity. The associations should be strong and varied [31]. The measurement of destination branding is complex due to the fact that it is relative and dynamic and, therefore, varies over time. Thus, the models developed so far to measure the brand image of a tourist territory are based on tangible and intangible elements. Tangible elements include price, accommodation, different tourist services. The intangible elements refer to the ideas and sensations that consumers experience when they see or hear about the destination [32].

The measurement of the image of the destination is based on tourist activities and their needs, including transport, various amenities, food, services and travel prices. The image can also be measured through the characteristics of the destination and its inhabitants, such as their hospitality, the political stability of the country, economic development and environmental management. The image can also be measured through the attributes of the destination and its inhabitants. These different elements make it possible to gauge the image of a destination not only in the eyes of tourists, but also in the eyes of the whole world [33].

5.1. Quantitative and qualitative approaches

The quantitative and qualitative approaches make it possible to measure the brand image of a destination. Four scales have been indicated by [16] to measure brand image: the attitude scale, the ranking scale, purchasing intentions and turnover evolution. The attitude scale refers to the attractiveness of the brand. The rating scale considers brand preference, as well as the characteristics that distinguish the destination from its competitors. Purchase intentions, on the other hand, provide information on the consumer’s conviction about the brand. The evolution of turnover gives indications concerning the volume of purchases of the brand and, hence, the realization of the purchase intention [16].

5.2. Direct and indirect approaches

The measurement of brand image can be done indirectly through the study of perceptions, or directly, through the analysis of preferences and direct measurements. For the indirect measurement approach, it is possible to base the measurement on mental representation and the individual’s ability to remember the brand. The consumer recognition or recalling of the brand allows the assessment of the brand’s strength. The stronger is the brand equity, the stronger and more positive are the associations. Moreover, brand image is considered strong in this indirect measurement approach when consumers associate many attributes with it. In other words, the indirect approach to brand measurement refers to the measurement of brand awareness. The latter has six dimensions: brand acceptance, brand memorization, first brands that come to the consumer’s mind, dominant brand (only one brand memorized), brand awareness and brand opinion [16].

6. Psychometric approach

Branding image is a multidimensional concept, particularly since it is often measured indirectly through its sources and its consequences. Unlike the various techniques already mentioned, psychometric measurements display the advantage of being more practical, more operational and above all more direct. In fact, it is a question of requesting consumers’ opinions, through a pre-established questionnaire. In other words, satisfaction’s surveys should be carried out among tourist consumers. The main measurement scale developed in this respect is the initiative of [34]. Nevertheless, the representations’ mental extraction from the consumer’s mind requires qualitative methods that are more rigorous than metric scales.

7. Brand’s image other measures

7.1. Explicit measures

When the consumer proceeds to a purchase decision, he tries to remember the advertising message and what the brand represents. It is above all the level of learning of the message that varies the result of this consumer research in classic or so-called Territorial Marketing. The effectiveness of an advertisement and the product or territory brand will be evaluated on the basis of the words memorized. This is an explicit measure, as it focuses on a single person and on what that person has retained from an explicit message.

Sometimes there may be a distortion between what the consumer has memorized, and the information given. In this case, the person does not correctly restitute what he or she has “learned” from the advertisement but adds other incorrect associations or fractions.

7.2. Implicit measures

Implicit measurement is useful to advertisers to determine what consumers know about their brand, regardless of the information source. Different types of measurement can be distinguished [18]:

- Memorization: measuring the effect of advertising exposure on brand memorization;

- Spontaneous notoriety: consists of measuring of advertising effectiveness by asking consumers to name brands for a product category.

8. Attitude study

Consists of determining the perception of the brand and not what consumers know about it. In this method, they make a judgment on the basis of the various criteria of the brand.

The aim of these pre-tests is to determine what makes consumers change their brand preferences. We strive to single out the elements that build consumer’s loyalty. Furthermore, classical theories indicate that there are strong and positive associations in the consumer’s mind that influence the general positive attitude towards the brand [35], [36]. The literature then suggests that the strength of the image, i.e. its ability to translate itself into utility and loyalty behavior, depends mainly on four attributes according to [37]:

- The strength of associations;

- The dominance of associations;

- The valence of associations;

- The cohesion of the associations.

Therefore, in [37] the author described that only associations considered by the consumer as positive, strong, unique, and coherent, build the strength of the image. For instance, they affect the overall preference for the brand or a re-purchase or recommendation behavior. By analogy, and mentioning in [38], we suggest that attitudinal fidelity to a destination depends on the strength and valence of its image. Ultimately, it is expected that a tourist with strong and positive associations with the destination brand would be more inclined to revisit it and recommend it to others.

After our review of the literature, it appears that there is no agreement on the dimensions that form the brand image of the tourist destination. In addition, many of the brand features of the touristic destination have remained vague and lacking of clarity.

This generalism causes a certain ambiguity between certain concepts close but different from the brand image of the tourist destination, which causes a problem in terms of its determinants and its scales of measurement. Therefore, the design of a tool (scale) to measure the image of the tourist destination presents a real challenge in order to guide future research and support the professionals in order to better manage their management system of the brand image of the touristic destination.

9. Research methodology

In order to develop a standardized measurement tool, we will adopt the advocated approach known as the Churchill’s paradigm [39]. The objective of this methodological approach is incorporating the knowledge of measurement theory and the appropriate techniques for improving it into an automatic procedure.

Similarly, Churchill’s paradigm offers the possibility of rigorously designing measurement instruments such as multi-scale questionnaires. To this end, we deemed it appropriate to use, first of all, a qualitative approach to explore the characteristics of the brand image of the touristic destination.

In our field investigation, we used the semi-directive interview for data collection. This method is favored given its great flexibility and the wealth of information it can produce [40].

According to the literature, we have elaborated an interview guide that includes about the respondent’s identification, age, gender and the determinants of the brand image of the touristic destination; the reputation of the touristic destination and ultimately the expectations of tourists towards (Rabat city).

The purpose of all these questions is to understand how the touristic destination is to understand how the brand image of the touristic destination is perceived by foreign tourists, and consequently to identify the different characteristics of the brand image of the touristic destination. Ten interviews were conducted with random tourists in Rabat city with average time duration of twenty (20) minutes. The population sample was characterized by female predominance (06 women and 04 men). The average age span is 28 years.

Afterwards, we have used a quantitative method. Indeed, in order to proceed in a methodological logic, we have formulated items based on all the items used in the different studies examined in the literature and the attributes collected after processing the information from the interviews (the results of the qualitative analysis will be dealt with in another research paper). Hence, a first version of the questionnaire was drawn up, then it was examined by two teacher-researchers in management sciences, and finally it was tested with 16 tourists from the city of Rabat.

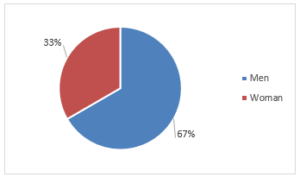

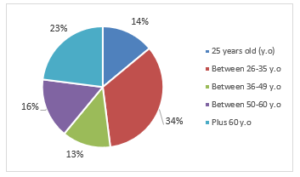

The comments collected made it possible, on one hand, to improve the questionnaire, and on the other hand, to underline the latest version of the questionnaire which consists of 26 items on a five-point Likert’s scale. Also, we also used exclusively affirmative sentences (positive statements) following Devellis’ recommendations. The data were collected in paper format. 454 usable questionnaires were collected. The representative population of the control sample is composed of 64% men and 36% women. The majority of the tourists are situated in the age group of 25 to 60 years old.

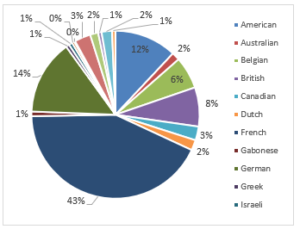

The following figures present the various information about our sample population (gender, age, country of origin):

Figure 1: Tourists distribution according to the gender

Figure 2: Tourists dispatching according to age

Figure 3: Tourists’ dispatching according to their nationality

10. Exploratory Factor Analysis

To elaborate our measurement scale, we have gone through several steps. First, we have verified the content validity of the scale for measuring the brand image of the tourist destination. Content validity tests aims to check whether the questionnaire’s different items are a good representation of the concept under consideration [41]. For this purpose, as explained before, we reviewed the academic literature to accompany and guide us in the questionnaire’s elaboration and to reach a measuring scale of the brand image of the touristic destination beforehand. Indeed, the large number of items constituting the measurement scale (16 items), their heterogeneity and the way in which they can be taken out of the dimensions, offer the researcher a choice between three types of analysis’ approaches:

- Independently, to examine each item by selecting only one item per theme;

- Aggregate all the items into a single scale;

- Undertake a factor analysis to identify the different underlying dimensions.

We have decided to introduce all items in a single scale without distinguishing between dimensions at the questionnaire level, in order to test the stability of the factor structure of the measurement scale we will use. The factor structure and the psychometric qualities of the scale of the tourist destination brand image were analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Social Sciences Package) 23 software, the data were subjected to principal component factor analysis with Varimax rotation in order to test the dimensionality of the construct.

The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is considered desirable in the development phase of a questionnaire in order to decrease the number of items and retain only keep those that allow the phenomenon to be characterized, particularly in order to identify the main factors [42].

The items purification deemed unsatisfactory was performed using the following elimination parameters: the rejection of items with a factor score of less than 0.3 and those with a high factor score on several factors [43]. The internal consistency reliability of the scale and its different dimensions was assessed by the Cronbach’s alpha analysis as well as the correlation level for dimensions with at least two items.

11. Results and discussions

We undertook an exploratory approach to determine the dimensions of the tourism destination’s brand. Firstly, we have prepared the number of variables, types of variables and finally the sample size.

Secondly, we looked at inter-item correlations. Then, we have measured the adequacy of sampling (KMO) and Bartlett’s sphericity Test. The results showed that the KMO index is 0,758. It is qualified as good. This index shows that correlations between items are of good quality. After this, the result of the Bartlett’s sphericity test is significant since p ˂ 0, 0005 (Table 1).

Table 1: KMO Index and Bartlett’s Test

|

Sampling precision measurement Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

0,758 |

| Approximate Khi-two | 3664,384 |

| Bartlett’s sphericity test ddl | 120 |

| Bartlett’s significance | 0,000 |

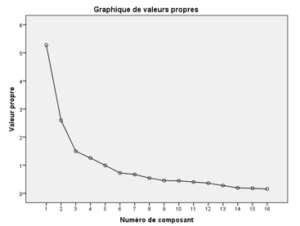

In order to extract the appropriate of factors for our scale, we first have analyzed the table of total variance explained, and we have noticed that 4 components have an eigenvalue higher than 1. The 4 factors explain 66.38% of the variance (Table 2). These factors are considered significant.

Table 2: Initial eigenvalues

| Component | Initial eigenvalues | ||

| Total | % of the variance | % cumulated | |

| 1 | 5,277 | 32,983 | 32,983 |

| 2 | 2,595 | 16,219 | 49,202 |

| 3 | 1,496 | 9,350 | 58,552 |

| 4 | 1,253 | 7,831 | 66,383 |

| 5 | 0,994 | 6,211 | 72,594 |

| 6 | 0,723 | 4,518 | 77,112 |

| 7 | 0,670 | 4,188 | 81,299 |

| 8 | 0,540 | 3,378 | 84,677 |

| 9 | 0,453 | 2,834 | 87,511 |

| 10 | 0,442 | 2,766 | 90,276 |

| 11 | 0,401 | 2,503 | 92,780 |

| 12 | 0,359 | 2,247 | 95,026 |

| 13 | 0,274 | 1,713 | 96,739 |

| 14 | 0,192 | 1,200 | 97,940 |

| 15 | 0,176 | 1,103 | 99,043 |

| 16 | 0,153 | 0,957 | 100,000 |

Secondly, and for more certainty, we have created a graphic from the eigenvalue using SPSS 23 (Figure 4) through the collapse layout and after examination of the Cattell’s Elbow rupture. We have noticed that there is a change after the third factor. For this purpose, we retain three (03) factors that lie before the abrupt change in the slope of the Cattell’s Elbow break for the analysis, since this criterion is precise than the eigenvalue criterion.

Figure 4: Initial eigenvalues

Table 3: Total variance explained through three dimensions (Extraction method: Principal Component Analysis)

| Component | Initial eigenvalues | ||

| Total | % of the variance | % cumulated | |

| 1 | 3,537 | 32,153 | 32,153 |

| 2 | 2,125 | 19,320 | 51,473 |

| 3 | 1,327 | 12,064 | 63,537 |

| 4 | 0,901 | 8,193 | 71,731 |

| 5 | 0,808 | 7,345 | 79,076 |

| 6 | 0,630 | 5,731 | 84,807 |

| 7 | 0,463 | 4,210 | 89,017 |

| 8 | 0,382 | 3,470 | 92,488 |

| 9 | 0,340 | 3,087 | 95,575 |

| 10 | 0,303 | 2,754 | 98,328 |

| 11 | 0,184 | 1,672 | 100,000 |

The exploratory analysis in Table3, shows three (03) factors according to [44], which leads to the selection of the number of factors with a value of 1or greater. A clear factorial solution appears, without overlap. Factors are easily interpretable. In addition, the selected items appear to represent the brand image of the touristic destination in terms of content.

According to the component matrix (Table 4), the first factor consists of 5 items that represent the abstract brand image [45]. The latter characterizes the destination which is Rabat city as an adventures’ destination judged by the foreign tourists interviewed, it is unique by its diverse touristic sites, A Sports destination because of the number of sporting events organized, namely the Rabat International Athletics Meeting, the Rabat International Marathon, the Hassan II Golf Trophy ,a city ranked second in the Maghreb region in terms of life quality after Tunis (capital of Tunisia), with a green belt of 1,063 hectares, Rabat city managed to double the global area of green spaces for each individual given the standard of the World Health Organization set at 10 square meters per person (Tests garden), Nazhat Ibn Sina, Hilton forest, Maamora,… and ultimately, an events’ destination (sporting, artistic and cultural).

In this regard, the author [46] argues that it is likely not all associations to the trademark have the same impact on behavior: associations involving symbolic benefits that are also abstract, would have a stronger influence than associations involving functional benefits.

The second factor represents the functional brand image, translated by the aspect of belonging to the territory and the local products, is composed of three items. These are related to the Peaks and Scents, Region City of the Rabat-Salé-Kénitra and the cultural activities namely Mawazine and the Rabat Jazz Festival for instance.

The third “Human and Intangible” factor is composed of three items. Rabat is a friendly city, a welcoming city, a wealthy city in terms of Historical Monuments (Mohammed-V Mausoleum, Oudayas Kasbah, Chellah, Rabat Saint-Pierre Cathedral, Hassan Tower, Mohammed VI Museum …)

Table 4: Components Matrix after rotation

| Component | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| IMA6 | 0,840 | ||

| IMA5 | 0,837 | ||

| IMF10 | 0,777 | ||

| IMA3 | 0,658 | ||

| IMF8 | 0,564 | ||

| IMF4 | 0,810 | ||

| IMA1 | 0,793 | ||

| IMF5 | 0,673 | ||

| IMA2 | 0,796 | ||

| IMF9 | 0,769 | ||

| IMF7 | 0,610 | ||

Table 5: Main Components’ Analysis (Varimax Rotation) of the Rabat Destination Branding Scale (n=454)

| Items | Components | Factors | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| IMA6. Adventures’ destination | 0,840 | Brand image Marque Symbolic, Abstract | ||

| IMA5. Unique destination | 0,837 | |||

| IMF10. Sports destination | 0,777 | |||

| IMA3. Green city | 0,658 | |||

| IMF8. Events (athletic, artistic, cultural). | 0,564 | |||

| IMF4. Spices and scents | 0,810 | Belonging to the Territory and Local Products | ||

| IMA1. Region’s city of Rabat Salé Kénitra | 0,793 | |||

| IMF5. Cultural activities | 0,673 | |||

| IMA2. Friendly city | 0,796 | Human capital Human, Capital Intangible | ||

| IMF9. Welcoming city | 0,769 | |||

| IMF7. Historical monuments | 0,610 | |||

The three factors explain 63,537% (Table 3) of the total variance explained for a KMO of, 758 (Table 1). The internal consistency reliability for each component is mentioned in Table 5. After identifying the items that constitute our measurement scale (Table 5). We presently want to verify whether this scale is stable over time and whether it makes it possible to properly measure the brand image of the destination we have identified. So, we are going to perform an internal consistency analysis.

Table 6 displays the Cronbach’s Alpha Index values for each component of the destination brand image. We observe that the value of the 1st component «Symbolic Brand Image» is 0,817, which is excellent, since it exceeds the minimum required threshold of 0,70 [47].

This beacon is arbitrary, but widely accepted by the scientific community. Consequently, we can claim that we obtain, for this scale composed of five elements, a satisfactory internal coherence. Similarly, the value of the 2nd component «Belonging to the Territory and Terroir Product» is 0,764, which is excellent. While the 3rd component’s value «Human and intangible capital» is 0,673, which is acceptable.

Table 6: Cronbach’s alpha coefficients

| Components | Cronbach’s alpha values |

| Symbolic brand image | 0,817 |

| Belonging to the territory and local product | 0,764 |

| Human and intangible capital | 0,673 |

After examining the tables of total statistics of the elements corresponding to each dimension of the measurement scale of the Brand Image of Rabat Destination (Appendix 1), we have noticed that the Cronbach’s alpha values of the first dimension improves (0,819 instead of 0,817) if we suppress item IMF8. Also, the Cronbach’s alpha value of the third dimension improves (0,705 instead of 0,673) if we discard item IMF7. So our measurement scale of the Brand Image of the Final Destination of Rabat is presented as follows:

Table 7: City of Rabat Brand Image measurement scale

| Factors | Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

| Symbolic brand image (abstract or functional) | IMA6. An adventures’ destination | 0,819 |

| IMA5.A unique destination | ||

| IMF10.Sports destination | ||

| IMA3. Green city | ||

| Belonging to the territory and local products. | IMF4.Spices and scents | 0,764 |

| IMA1.Region city of Rabat Salé Kénitra | ||

| IMF5. Cultural activities | ||

| Human and intangible capital. | IMA2.Friendly city | 0,705 |

| IMF9.Welcoming city |

11.1. Study results and implications

The results obtained show that functional and abstract associations jointly form the brand image of Rabat city in the foreign tourists’ memory and that abstract associations are more significant in the choice of the destination. These results confirm that the brand image is constituted of several attributes linked to the associations, whether functional or abstract (the belonging to the territory and local product 0.764). The respondents consider that they are part of this destination and that local products remain a strong argument in the choice of destination. These data make it possible to mobilize a different approach in the management of the Rabat destination which prioritizes a diversified offer for foreign tourists capable of enriching this dimension of belonging and preference for local products and improving their quality.

The resources of the Rabat city destination mentioned in this study represent important distinctive and specific qualities in the overall satisfaction for the visit to a touristic location[48]. Moreover, the attributes linked to associations are a real means in order to develop and strengthen the brand image and, consequently, improving the attractiveness of the destination[49]. The results of this study represent a real reference for the managers of the Rabat destination and the Moroccan tourist sector for new prospects for the segmentation of the touristic offer and the opening up of new markets.

Conclusion

The aim of this research is suggesting a measurement scale of the touristic destination image in a Moroccan setting (Rabat city). To achieve this goal, we have conducted two empirical investigations. First, we have conducted a qualitative exploratory study in the form of ten semi-directive interviews, during July 2019, with a multi-nationality tourists visiting Rabat. Each interview lasted about twenty minutes. Then we have performed a quantitative study among 454 foreign tourists in Rabat during the time period from October to December 2019, and our results show:

- The existence of two different tourist’s profiles based on the brand image they develop in their memory, a functional or abstract image and that the abstract brand image (Rabat unique city, city of adventure,0,819 of Cronbach’s alpha) is more significant than the functional image (sports city…).These results are more compliant with those of [47] who suggested that not all associations with the brand have the same impact on tourist’s behavior, with so-called symbolic or abstract associations having a stronger influence than those relating to functional benefits;

- The brand image, whether functional or abstract, constitutes an enormous potential for the Rabat destination (factor of belonging to the territory and terroir’s product) of our model, 0,764);

- Our measurement scale suggests three (03) complementary factors, 9 items to measure the brand image of Rabat city. The three factors explain 63,537% (Table 3) of the total variance explained for a KMO of 0,758 (Table 1);

- At the managerial level, this study will enable the stakeholders of the national tourism sector to draw the necessary conclusions to segment the tourist’s market at the level of Rabat city and at the national level according to the identified behaviors and preferences.

Likewise, all scientific research, our study displays some limitations which constitute as many threads of investigation. In fact, the scale has only been tested on one category of foreign tourists – those of Rabat city – and it is therefore appropriate to generalize the measure to several cities. Such an approach can improve the predictive validity of our scale at the national level.

Certain other research perspectives related to the results can be suggested. It would be interesting to study the structural relationships between the 3 factors of our model and to test their impact on other concepts such as attachment to the destination.

- M. Abakouy, M. Khatib, “Positionnement marketing et développement de la ville de Casablanca en tant que destination touristique,” 13, 2016.

- B. Meyronin, J. Gayet, G. Collomb, Marketing territorial: enjeux et pratiques, Vuibert, Paris, 2015.

- A.E. Khazzar, H. Echattabi, “Les pratiques du marketing territorial dans le contexte marocain: Eléments de réflexion,” 16(1), 14, 2016.

- P. Marcotte, L. Bourdeau, E. Leroux, “Branding et labels en tourisme: réticences et défis,” Management Avenir, n° 47(7), 205–222, 2011.

- M.U. Proulx, D. Tremblay, “Marketing territorial et positionnement mondial,” Geographie, economie, societe, Vol. 8(2), 239–256, 2006.

- C. Camelis, “L’influence de l’expérience sur l’image de la marque de service,” Vie sciences de l’entreprise, N° 182(2), 57–74, 2009.

- F. Smaoui, “Les déterminants de l’attachement émotionnel à la marque: Effet des variables relationnelles et des variables relatives au produit,” 27, 2008.

- F. Cusin, J. Damon, “Les villes face aux défis de l’attractivité. Classements, enjeux et stratégies urbaines,” Futuribles, (367), 25–46, 2010, doi:10.1051/futur/36725.

- T. Albertini, D. Bereni, G. Luisi, “Une approche comparative des pratiques managériales de la Marque Territoriale Régionale,” Gestion et management public, 5(2), 41–60, 2017.

- C. Lai, I. Aimé, La marque, 2016.

- H. Azouaoui, A. Ismaili, “L’identité de la marque de territoire et décision de localisation des entreprises: Approche par la littérature,” 21, 2015.

- E. Belkadi, “Marketing Territorial de Casablanca: Etude de l’Image de Marque [ Place Marketing: The Brand image of Casablanca ],” 13(3), 11, 2015.

- É. Tortochot, G. Alt, Design(s): de la conception à la diffusion, Bréal, Rosny-sous-Bois, 2004.

- A.-C. Marchat, C. Camelis, “L’image de marque de la destination et son impact sur les comportements post-visite des touristes,” Gestion et management public, 5/3(1), 43, 2017, doi:10.3917/gmp.053.0043.

- Malaval Philippe, Pentacom: communication corporate, interne, financière, marketing b-to-c et b-to-b / Philippe Malaval,… Jean-Marc Décaudin; avec la collaboration de Christophe Bénaroya,… Jacques Digout,…, 3e édition, Pearson, Paris, 2012.

- A. ABYRE, Y. ALLAOUI, “Savoir mesurer l’image de marque pour pouvoir l’améliorer,” Management Research, 7.

- J.-L. Leignel, E. Ménager, S. Tablonsky, Performance durable de l’entreprise. Piliers, évaluation, leviers – Jean-Louis Leignel,Emmanuel Ménager,Serge Tablonsky, Dec. 2020.

- H. Berrehail, E.H. Boukalkoul, “Concept de l’image de marque,” . . May, 5, 19, 2016.

- P.S. Manhas, L.A. Manrai, A.K. Manrai, “Role of tourist destination development in building its brand image: A conceptual model,” Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science, 21(40), 25–29, 2016, doi:10.1016/j.jefas.2016.01.001.

- J. Lacœuilhe, “L’attachement à la marque: proposition d’une échelle de mesure,” Recherche et Applications En Marketing, 15(4), 61–77, 2000.

- G. Prayag, S. Hosany, K. Odeh, “The role of tourists’ emotional experiences and satisfaction in understanding behavioral intentions,” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2, 118–127, 2013, doi:10.1016/j.jdmm.2013.05.001.

- G. Dunne, S. Flanagan, J. Buckley, “Towards an Understanding of International City Break Travel,” International Journal of Tourism Research, 12, 409–417, 2009, doi:10.1002/jtr.760.

- V. Minghetti, F. Montaguti, Cities to Play: Outlining Competitive Profiles for European Cities, Springer, Vienna: 171–190, 2010, doi:10.1007/978-3-211-09416-7_10.

- M. Gigot, “La patrimonialisation de l’urbain,” 9, 2012.

- F.D. Grandpré, “Attraits, attractions et produits touristiques: trois concepts distincts dans le contexte d’un développement touristique régional,” Téoros. Revue de recherche en tourisme, 26(26–2), 12–18, 2007.

- T. Vo Thanh, V. Kirova, R. Daréous, “L’organisation d’un méga-événement sportif et l’image touristique de la ville hôte: une perspective par le concept de transfert d’image,” Téoros: revue de recherche en tourisme, 33(1), 87–98, 2014, doi:https://doi.org/10.7202/1036722ar.

- H. Kim, J.S. Chen, “Destination image formation process: A holistic model,” Journal of Vacation Marketing, 22(2), 154–166, 2016, doi:10.1177/1356766715591870.

- C. Dubois, M. Cawley, S. Schmitz, “The tourist on the farm: A ‘muddled’ image,” Tourism Management, 59(C), 298–311, 2017.

- P. Cottet, M.-C. Lichtlé, V. Plichon, J.-M. Ferrandi, “Image d’hospitalité des villes touristiques: le rôle de la communication,” Recherches en Sciences de Gestion, 108(3), 47, 2015, doi:10.3917/resg.108.0047.

- S. Zenker, E. Braun, S. Petersen, “Branding the destination versus the place: The effects of brand complexity and identification for residents and visitors,” Tourism Management, 58, 15–27, 2017, doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2016.10.008.

- H. Guizani, P. Valette-Florence, “Proposition d’une mesure psychométrique du capital client de la marque,” Marche et organisations, N° 12(2), 11–41, 2010.

- P. Scorrano, M. Fait, L. Iaia, P. Rosato, “The image attributes of a destination: an analysis of the wine tourists’ perception,” EuroMed Journal of Business, 13(3), 335–350, 2018, doi:10.1108/EMJB-11-2017-0045.

- H. Zhang, Y. Wu, D. Buhalis, “A model of perceived image, memorable tourism experiences and revisit intention,” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 326–336, 2018, doi:10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.06.004.

- B. Yoo, N. Donthu, Developing a Scale to Measure the Perceived Quality of an Internet Shopping Site (PQISS), Springer International Publishing, Cham: 471–471, 2015, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-11885-7_129.

- C. Viot, “David Aaker: Efficacité publicitaire, capital marque, comportement du consommateur et lien marketing-finance,” 21, 1994.

- K.L. Keller, “Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity,” Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22, 1993, doi:10.1177/002224299305700101.

- S. Changeur, Le territoire de marque: proposition et test d’un modèle basé sur la mesure des associations des marques, These de doctorat, Aix-Marseille 3, 1999.

- K. ZENAIDI, J.-L. Chandon, “Une nouvelle mesure du capital marque par une approche formative,” Revue Tunisienne Du Marketing, 1(1), 8–21, 2009.

- G.A. Churchill, “A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs,” Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73, 1979, doi:10.2307/3150876.

- M.B. Miles, A.M. Huberman, Analyse des données qualitatives, De Boeck Supérieur, 2003.

- L. Dialogues, Market – 3ème édition – Études et recherches en… – Yves Evrard, Bernard Pras, Elyette Roux – Dunod, Dec. 2020.

- A.B. Costello, J. Osborne, “Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis,” 7, 10, 2005, doi:10.7275/JYJ1-4868.

- P. Roussel, F. Wacheux, Management des ressources humaines: méthodes de recherche en sciences humaines et sociales / sous la direction de Patrice Roussel et Frédéric Wacheux, de Boeck. Bruxelles, 2005.

- H.F. Kaiser, “The varimax criterion for analytic rotation in factor analysis,” Psychometrika, 23(3), 187–200, 1958, doi:10.1007/BF02289233.

- J.L. Crompton, “Motivations for pleasure vacation,” Annals of Tourism Research, 6(4), 408–424, 1979, doi:10.1016/0160-7383(79)90004-5.

- M. Korchia, “Une nouvelle typologie de l’image de marque,” 16ème congrès international de l’Association Française du Marketing, 18, 2001.

- J.C. Nunnally, Psychometric theory, 2nd Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1978.

- A.F. Lecompte, M. Trelohan, M. Gentric, M. Aquilina, “Putting sense of place at the centre of place brand development,” Journal of Marketing Management, 2017.

- R.H. Taplin, “The value of self-stated attribute importance to overall satisfaction,” Tourism Management, 33(2), 295–304, 2012, doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2011.03.008.