An Analysts’ Skills: Bespoke Software vs Packaged Software at Small Software Vendors

Volume 5, Issue 6, Page No 1021-1026, 2020

Author’s Name: Issam Jebreena)

View Affiliations

Department of Software Engineering, Zarqa University, Zarqa, 13110, Jordan

a)Author to whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: ijebreen@zu.edu.jo

Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 5(6), 1021-1026 (2020); ![]() DOI: 10.25046/aj0506123

DOI: 10.25046/aj0506123

Keywords: Small Software Vendors, Packaged Software, SMEs, Analysts Skills

Export Citations

SMEs usually succeed in today market since they achieve unique things in the business market. Therefore, SMEs look to keep their business benefit by avoiding any regulation conducted of software. Executed software packaged at SMEs consequently provides obstacle concerning to misfits between software services process and SMEs business process. Hence software analysts’ skills are a critical factor for successfully overcome obstacle relating to misfits. This study conducted a questionnaire by quantitative data to understand in-depth analysts’ skills need during the process of software mismatch adjustment. Based on our analysis of the data gathered, we represented a list of skills that analysts applied to detect misfits between software service provided and SME’s business process. This study, therefore, explains skills that analysts used to overcome the obstacle of software implementation at SMEs.

Received: 10 October 2020, Accepted: 21 November 2020, Published Online: 08 December 2020

1. Introduction

In current years Small Software Vendors (SSVs) for Packaged Software (PS) is increased they are competitive by selling their products to large numbers of SMEs [1]. SSVs have, therefore activated to mark SMEs less complicated products that have developed [2]. SMEs are an essential business target many SSVs as mentioned by [3] SMEs “with less than 500 employees provided 51 per cent of all employment in the USA as of March 2004 and 64 per cent of all Canadian private sector employment in 2005. In the European Union, firms with 250 employees or less provided 67 per cent of employment” [3]. A study by [4] stated that SMEs subsidize to economic growing to a great degree and incessantly generating employ chances through the business. SMEs are an essential economies part, SMEs surface particular challenges once they are implementing a PS for their business [5, 6].

SMEs seem to remain different comparing to large companies in several points [7]. Some individual features of SMEs contain types of ownership, business structure, and target market [7]. Several studies have stated that SMEs have limited IT knowledge and resource regarding IT adaptation/adoption [7]. These obstacles lead to the implementation of PS presence a challenge for SMEs. Researchers of SSVs have found that they cannot conduct the process of implementing PS at a large business to SMEs [7]. Regardless of the importance of Packaged Software (PS) conducting it is recognized by these SSVs researchers, there is a little investigation to exploring these obstacles. In particular, considerations about SMEs hardly investigate in the SSVs literature and the question of how SSVs have overcome these obstacles and what are the analysts’ skills to successfully conducted a PS at SMEs [2].

In [8], the author conducted research relating to the soft skills of software development staff across four significant parts of the world, which included North America, Asia, Europe, and Australia. researchers conducted on the belief that soft skills are complementary to technical skills, and thus essential attributes for IT staff to have [8] claimed that during different project stages, incredibly soft skills required. Therefore, various team members should have a variety of soft skills. Those skills were communication skills, interpersonal skills, analytical and problem-solving skills, organizational skills, innovative skills, adaptability to change, and the ability to work in a team and to work independently. Other study by [9] regarding analysts’ communication skills a key factor for requirement gathering, they found that knowledge about business process of users’ companies and domain knowledge different business are the most critical factor for requirements gathering.

It can claim that none of the previous studies related to analysts’ skills focuses on any detail on how analysts manage software specificity and generality when implementing packaged software compare to bespoke software [10]. Hence, they do not provide any overview of what domain knowledge and estimation skills required from analysts implementing packaged software. Nor do they focus on the fact that there are pronounced differences between bespoke software and packaged software. Therefore, there is a need for an investigation of which domain knowledge and estimation skills are required when analysts manage software specificity and generality.

This study provides an overview of analysts’ skills at small software vendors (SSVs) regarding PS conducted at SMEs. It explores this area from the perspective of small software vendors. In focusing on an understanding of analysts’ skills at SSVs, we construct a questionnaire by quantitative data to represent high demand for skills used during the conduct of PS at SMEs. This study organized as follows: review literature; research method; results and discussed, conclusion and considers future work.

2. Study Background

The purpose of this section is to provide a perception of the theoretical concept of software packaged; analysts’ skills and the processes involved, and packaged software implementation. In this section, we assumed that PS conducted at SMEs depend on a set of techniques such as software integrations, customization, adoption/adaption, and the identification of misfits between PS services and SMEs business process. Hence these processes require from PS analysts to interact with SMEs employees that require different skills. Additionally, in this section, during the review of previous studies relating to packaged software, we present and define several PS elements. There are several elements involved in the process of PS conduction such as PS customization, adaption, and adoption [11]. If the efficiency of these elements enhanced, this might lead to the increased success of PS conduction at SMEs.

The market of PS is the fastest rising business for small software vendors (SSVs), [12] study shown that PS market for SSVs is growing to $64.88 billion in 2009. Therefore, such procedures of software may be very targeted to viable SMEs business [12].

Small software vendors shape their business to developing small packaged software (SPS) instead of bespoke software. However, those vendors have faced new management development challenges [13], [14] recognized the lack of in research investigate dedicated to reviewing the packaged software area, he recognizing main differences between the packaged software development process and bespoke software. The study acknowledged variances at four levels that contain “industry forces, approaches to software development, work culture, and development team efforts”. His argument of the conflicts increased by recognizing and discoursing the five different participant groups participate in both bespoke and PS development. In [14], the author stated that “custom IS are those made by either an organization’s internal staff or by direct subcontract to a software house”. The study goes on to classify ERP product as the wildest rising example of a packaged software product. PS requires wide modifying for their application, which regularly involves the help of variances parties such as training, consultants, and support staff [15-17].

When associating noticeable differences between bespoke and PS developing process, Sawyer states that time pressures are a main critical factor for PS development rather than software cost compare to bespoke software. Meanwhile, the successful implementation criteria for PS software is different compare to bespoke software, PS software assesses by software profit, several target markets, and famous the product. However, successful implementation criteria for bespoke software, that is measured by specific company satisfaction about the services provided by the software. Moreover, the PS development is relying on developers’ experience of business domain knowledge, but bespoke software is depending on the needs of users.

In [14-17], and other research by [13] and [18], the authors stated that software companies treat PS as a product. Therefore, the effort is on carrying a product that can sell to many, and the product vision relying on releases planned. Meanwhile, bespoke software, the effort is on carrying on software development process in order to have a user’s stratification. The primary assumption of these researchers is that the process of software development is different from PS and bespoke software, the most distinct is at software company structure level, the process of development regarding users’ involvement, the culture of work, development effort by software teams.

In recognition of these concerns, systematic studies have been undertaken in the current year to increase the success of the method of packaged software creation [11]. For example, in order to understand the process of requirement engineering for PS, [14] researched the process and challenges of the requirement engineering process for PS in Swedish software companies. Many of the problems they exposed were exclusive to PS and not suitable for personalized applications. They therefore noted that specifications for engineering approaches carried out by a tailor-made software team might not be especially helpful in supporting the development process for PS. In another study by [10], it was reported that the personalized process of software requirement engineering and the methods used have inadequate utility for PS.

For analysts, these present a primary challenge in creating the preliminary software for future marketing. However, as possible consumers are accepted, they have become the primary source for the selection of requirements. Nevertheless, the original software / product specifications are typically generated by the creators of PS, who have used their thoughts on business goals, understanding of the business domain or a product vision [14]. This method makes it rational to assume that not all packaged software services and features are suitable for the business of SMEs [15]. In other words, there can be misfits between the business processes of PS services and SMEs. In order to minimize any unintended effects, SSVs and recognized SMEs should reduce the possible gaps (a skills require from analysts) in the PS to be effective.

Therefore, several studies conducted to investigate the critical success factors (CSFs) for PS implementation. Instead of that, [19] surveyed 86 organizations by an essential characteristic of success PS implementation to generate the most important critical success factors for PS implementation. They propose that the CSFs list may include assistance leaders of PS projects to better apply inadequate resources by using the CSFs that are existences at SMEs and have a primary effect on the PS success implementation. The study offers a brief clarification of critical success factors, along with an interpretation of the value of each aspect. (1) Management support, (2) product champion, (3) consumer training, (4) expectation management, and (5) supplier / customer relationships are the leading five variables recognized.

The purpose of [17] is not only to test the accuracy of the top 10 list of [16], but to build on the list by theorizing some of the causal relationships between the individual CSFs. The research question was: (1)” Can the list of [16] helps to gain a deeper understanding of the root causes of success and failure in the implementation of ERP?” [17] agreed to evaluate the top 10 CFSs that have a mix of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ success elements, and they noted that the most significant factors are: top management support, project team experience, interdepartmental cooperation, consistent expectations and goals, and project management. Any of the stuff on the top 10 list were originally ranked lower by [16]. Still, after feedback received from 52 company managers approached to provide input by [17], he moved the ranking up. In other IT literature related to implementation, many of the items on the top 10 list also seem to appear frequently.

In [4], the author reviewed in the words of SMEs, the most recent literature on the adoption and application of ERP systems in SMEs. Noting that ERP systems have now been almost universally implemented by large organizations, [4] said that ERP vendors have now begun to turn their attention to small-medium-sized organizations (SMEs). Although ERP systems can help small and medium-sized enterprises, “the risks for small and medium-sized enterprises of implementing an ERP system are different because small and medium-sized enterprises are likely to have limited resources and business features that are different from those of large organizations.” In [4], the author provided insight into the areas missing from the current ERP adoption analysis in SMEs and provided expertise to assist ‘professionals, suppliers and SMEs’ while embarking on ERP projects.’ In fact, ‘Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) recognized as fundamentally different circumstances relative to large enterprises'[18] have not published any relevant literature on the implementation process in SMEs [4].

The literature mentioned by [4] shows that academic research has shown a significant increase in the use of ERP in small and medium-sized enterprises, and that case studies and surveys are the most common methods used in research papers on this topic. They discovered that the implementation method was the most discussed in the literature on ERP use in SMEs. This result contributes to the crucial topics of literature debate within larger organizations on ERP systems. However, in the literature on the use of ERP in SMEs, the adoption decision, the acquisition process, and the use and maintenance step are also given acceptable levels of emphasis. The processes for which literature has been rather scarce or non-existent are ERP evolution and ERP system retirement [4]. Further suggested that only two published papers found ‘in-house built systems’ to be a viable option for small and medium-sized enterprises. At the same time, “normal ERP solutions could require straight lines and a lack of versatility for particular SMEs.” It is therefore safe to say that, from the point of view of SSVs, the existing literature has paid little attention to the implementation of PS activities by SSVs.

In [5], the author make some more remarks about the existing literature after giving specific critical of the reviewed literature and suggest more avenues for research. First of all, they say that, even though 77 papers identified and examined, this was still a minimal number of documents to be conducted within ten years on the subject, considering the increasing significance of ERP technology in response to SMEs. They conclude that “in contrast with ERP in LEs, SMEs have not earned sufficient attention.” “that include a lack of” ex-ante cost estimate, economic viability and investment appraisal studies of ERP ventures “research, a lack of contrast between” SME-specific ERP and general ERP systems ” or “industry-specific ERP vs general ERP packages” studies.

In [4], the author found that only a few studies were performed on the growth of ERP systems in small and medium-sized enterprises, and no study on small and medium-sized enterprises discussed the implementation phase of an ERP system. Finally, while they found 77 articles related to ERP systems in small and medium-sized enterprises, [4] recorded that the majority of small and medium-sized enterprises were engaged in traditional manufacturing, and that it could be important to achieve results compared to different industries, or it could be beneficial if recent studies on the use of the ERP system in small and medium-sized enterprises were carried out. They also found that almost all research studies have found that businesses are concentrated in America, Australia, Europe, and Asia. There has been a shortage of studies that examine SMEs in Africa or the Middle East. Therefore, a one-sided viewpoint (in data collection) has been adopted by current literature, e.g. on the client-side, whereas other views might strengthen the perception of such phenomena. Any studies that examine instances of failed ERP implementations within SMEs are also absent.

After reviewing the literature on this subject, package software often created in many sequential releases but that there is intense competition among various formats within the packaged software industry. This is only one of the components unique to packaged software, which explains part of why the features of packaged software vary significantly from the elements of customized software. Alternatively, there are potential clients, an imagined group of people who may fit the profile of the product’s intended customer. The elicitation of specifications from this group of users and customers is one of the tasks that separates bundled applications from bespoke. The elicitation of such requirements is primarily handled by ads, technical assistance, user groups and trade publication testers. Therefore, it seems reasonable to say that not all the applications functionalities will be appropriate for the customers’ business requirements. In other words, when packaged software is implemented by tech firms, there would be inconsistencies between the features provided by packaged software and customers ‘ business requirements. Therefore, different skills are required from PS analysts in order to successfully implement a PS.

Packaged program development can be a massive undertaking that needs a substantial amount of time, effort and adjustments in the implementation organization. The implementation of the PS is often the single largest project ever launched by an organization.

3. Research Design

A survey questionnaire on the skills adopted was used to collect quantitative data based on [8-10] and shows the skills required in PS. The skills mentioned in the table below in terms of how analysts used them.

In cases where expectations of one’s competence affect the way he or she interacts, the Self-report instruments are suitable [20]. Besides, claimed that people could have more contextual information about themselves than anyone else does, offering some encouragement for the use of such a system.

As show in table 2, our sample of software companies involved in this research covers the area of software development, integration of systems, and localization of software. A total of 60 participants presented, including analysts and developers. Seven of the participants made up of team leaders.

Table 1: Survey Questionnaire Sample

| Skills | |

| Skills & Knowledge | Assessment Level |

| Communication skills | Low, Moderate, and High |

| Interpersonal skills | Low, Moderate, and High |

| Organizational skills | Low, Moderate, and High |

| Team Player | Low, Moderate, and High |

| Ability to Work Independently | Low, Moderate, and High |

Table 2: Sample descriptions

| Area | %Sample | Participants | Experiences |

| development | 85% | Team Leader | 12% |

| Integration | 70% | Analysts & Developers | 75% |

| localization | 40% | ||

| Experiences | 12% | 75% |

System analysts and developers were most of the participants at the same time. Most participants had a cumulative experience of 3-10 years in the industry, while a few had the experience of more than ten years. Most of the participants had experience working concurrently as researchers, designers, and developers. As analysts only, some participants had the expertise and some as developers only. Most participants had experience with software for company applications and software for database systems.

The data has analyzed as the percentage of participants answers regarding skills required for bespoke software and packaged software.

Table 3: Responses regarding software type.

| Software type | #Responeses |

| Bespoke | 27 |

| Packaged | 33 |

As show in table 3, it was 27 responses from bespoke software analysts and developers and 33 responses from packaged software. The top of questionnaire, the participants were chosen the type of software they would like to fulfill up the questionnaire for.

4. Result & Discussion

The table 4 below follows a list of skills adopted by [8-10] and shows the skills required in PS vs Bespoke software. The skills mentioned in the table in terms of how analysts used them.

It can be seen from the table 4 that the skills generally required of analysts practicing Packaged software implementation (PSI) are much the same as those required of analysts engaged in bespoke software, but that some of the skills are required to be practiced at a higher level or to use more often. There are some differences involved in terms of how skills are needed and practiced about skills and knowledge, development skills, software knowledge, business skills, problem-solving, and hardware knowledge.

Table 4: Skills Assessment Level

| Skills | ||

| Skills & Knowledge | Bespoke software | PS |

| Communication skills | High | High |

| Interpersonal skills | Moderate | High |

| Organizational skills | Low | Low |

| Team Player | Moderate | Moderate |

| Ability to Work Independently | Moderate | High |

| Development skills | ||

| Programming | High | High |

| General knowledge of development | High | High |

| Implementation | High | High |

| Operations/maintenance | High | High |

| Design | Moderate | Moderate |

| Analysis | High | High |

| Documentation | Moderate | Moderate |

| Development methodologies | Moderate | Moderate |

| Integration | Low | High |

| Knowledge of technological trends | Low | High |

| Quality assurance | Low | High |

| Software | ||

| Programming language | High | High |

| Database | High | High |

| Operating systems / platforms | Moderate | High |

| Packages | Moderate | High |

| General knowledge of s/w | Moderate | Moderate |

| Business skills | ||

| General knowledge of business | High | High |

| Function specific | Moderate | High |

| Industry specific | Low | High |

| Enterprise-wide | Low | High |

| Problem Solving | ||

| Technical expertise | Low | High |

| General problem solving | Low | High |

| Adaptive / flexible | Low | Low |

| Analytical / critical / logical | Low | High |

| Customer-oriented | Low | High |

| Hardware | ||

| Server | Low | High |

| General knowledge of h/w | Low | Moderate |

| Desktop/PC | Low | Moderate |

| Devices/printers/storage | Low | Low |

Note that the bolded italics in the PS column show the differences

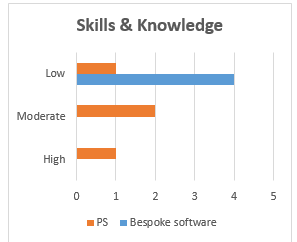

Bespoke software requires the analyst to show a certain level of skills and knowledge related to communication skills, interpersonal skills, organizational skills, ability to work in a team, and ability to work independently. PSI requires the same kinds of skills, but some of these skills demanded at a different level as shown in figure 1.

For example, the analyst engaged in PSI will need to meet higher demands in terms of their development of interpersonal skills, and their ability to work independently.

Figure 1: Skills & Knowledge

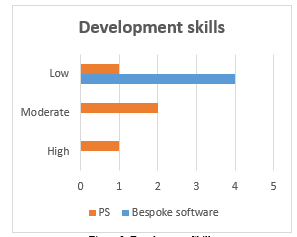

Figure 2: Development Skills

Figure 3: Software

When it comes to development skills as shown in figure 2, the analyst engaged in PSI will need to have a higher level of skill when it comes to dealing with software integration, quality assurance, and knowledge of technological trends. In bespoke software, these skills only required at a ‘low’ level. In PSI, the need for these skills categorized as ‘high’.

When it comes to knowledge of software and the ability to use the software as shown figure 3, the skills required of bespoke software analysts and PSI analysts also differ. In Bespoke software, the analyst’s knowledge about operating systems/platforms and packages only needed to be at a ‘moderate’ level. In PSI, these skills required to be at a ‘high’ level.

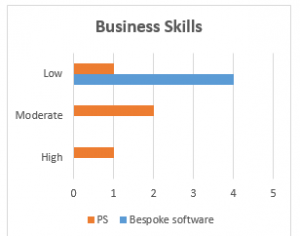

Bespoke software and PSI also require a different use of business skills as shown in figure 4. The analyst engaged in bespoke software needs a high level of knowledge about the business, as does the analyst employed in PSI.

Figure 4: Business Skills

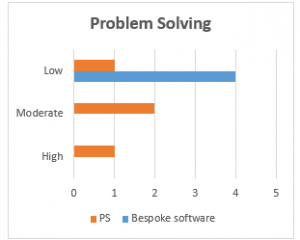

Figure 5: Problem Solving Skills

However, in bespoke software, the analyst needs only a ‘moderate’ understanding of specific functions. In PSI, this knowledge of particular procedures must be high. In bespoke software, the analyst’s industry-specific and enterprise-wide skills are ‘low’, whereas, in PSI, they practiced at a ‘high’ level.

The skills related to ‘problem-solving’ also differ between bespoke software and PSI as shown in figure 5.

The ability to be adaptable or flexible required at the ‘low’ level in both forms of RE. Several other skills needed to differ in terms of use, however. For example, skills related to general problem-solving, technical expertise, the ability to be analytical, critical, or logical, and to engage in customer-oriented problem solving practiced at a ‘low’ level in bespoke software. These same skills practiced at a ‘high’ level in PSI.

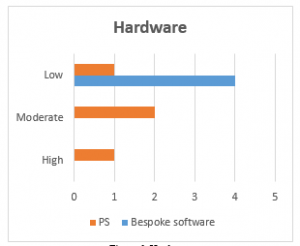

Lastly, analysts’ skills related to hardware also differ as shown figure 6. The analyst doing bespoke software requires only a ‘low’ level of skills concerning general knowledge about hardware, knowledge about servers, desktop PCs, and knowledge about devices and storage. The requirement of these skills is slightly different for the PSI analyst. In PSI, the analyst has ‘moderate’ skills concerning general knowledge about hardware, desktop computers, and PCs. As in bespoke software, they need only ‘low’ knowledge about devices, storage, and printers. However, they will need to have a ‘high’ level of knowledge about servers.

Figure 6: Hardware

5. Conclusion

This study provides an account of the distinction between the skills of analysts for packaged software and bespoke software with an emphasis on the activities of analysts. Through this report, we offer a detailed discussion of the skills of analysts required to be effectively implemented by PS and the challenges faced when implementing packaged software at SMEs. The numerous factors involved in seeking buyers, eliciting requirements and detecting misalignments, designing a packaged software product, and updating or adapting existing packaged software have been addressed.

The expertise and abilities of analysts to communicate with consumers should be considered as crucial factors when attempting to enhance the actions and results of the application of the PS. By enhancing their development skills, in particular integration, awareness of technical developments, and quality assurance skills, analysts will gain confidence, strengthen their critical thinking capabilities and problem-solving skills, and enhance their ability to connect, engage, and cooperate with the implementation of PS.

Business skills are the most important for understanding the business process of SMEs based on the responses of our 60 participants. In view of this, it is important to improve well-developed function-specific skills to minimize misunderstandings and increase the efficacy of such communication. In addition, the involvement of analysts with inadequate skills to work efficiently during the implementation of PS, showing weak or poorly performed interaction skills, may also lead to fragmented teams and disagreements between team members, resulting in an unsatisfactory experience for both users and analysts. This analysis of skills analysts in PS can help to shed light on areas of practice that can be focused on by an analyst to reduce the risk of problematic implementation of PS. Future studies will seek to establish a theoretical framework that describes the interaction techniques that analysts apply during the production and implementation of the PS, as this research is ongoing.

- V. Morabito, S. Pace, and P. Previtali, “ERP marketing and Italian SMEs,” European Management Journal, 23, 590-598, 2005. doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2005.09.014.

- O. Zach and B. E. Munkvold, “Identifying reasons for ERP system customization in SMEs: a multiple case study,” Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 25(5), 462-478, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1108/17410391211265142

- F. Kramer, T. Rehn, M. Schneider, and K. Turowski, “ERP-adoption within SME—challenging the existing body of knowledge with a recent case,” in Multidimensional Views on Enterprise Information Systems, ed: Springer,12, 41-54, 2016, doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27043-2_4

- S. B. Gunjati and C. Adake, “Innovation in Indian SMEs and their current viability: A review,” Materials Today: Proceedings, 28(4), 2325-2330, 2020, doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.04.604.

- M. Haddara and O. Zach, “ERP systems in SMEs: A literature review,” in 2011 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,1-10, 2011, doi: 10.1109/HICSS.2011.191

- B. Snider, G. J. da Silveira, and J. Balakrishnan, “ERP implementation at SMEs: analysis of five Canadian cases,” International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 29(1), 4-29. 2009, https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570910925343.

- S. Laukkanen, S. Sarpola, and P. Hallikainen, “Enterprise size matters: objectives and constraints of ERP adoption,” Journal of enterprise information management, 20(3), 319-334, 2007, https://doi.org/10.1108/17410390710740763.

- F. Ahmed, L. F. Capretz, S. Bouktif, and P. Campbell, “Soft skills requirements in software development jobs: A cross-cultural empirical study,” Journal of systems and information technology, 14(1), 58-81, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1108/13287261211221137.

- I. Jebreen and A. Alqerem, “Critical proficiencies for requirements analysts: reflect a real-world needs,” Int. Arab J. Inf. Technol., 15(3A), 626-632, 2018,

- I. Jebreen and A. Al-Qerem, “Empirical Study of Analysts’ Practices in Packaged Software Implementation at Small Software Enterprises,” International Arab Journal of Information Technology (IAJIT), 14, 2017.

- M. Tamimi and I. Jebreen, “A Systematic Snapshot of Small Packaged Software Vendors’ Enterprises,” International Journal of Enterprise Information Systems (IJEIS), 14(2), 21-42, 2018, doi: 10.4018/IJEIS.2018040102

- L. Staehr, G. Shanks, and P. B. Seddon, “An explanatory framework for achieving business benefits from ERP systems,” Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13(6), 2, 2012, doi: 10.17705/1jais.00299

- T. Gorschek, A. Gomes, A. Pettersson, and R. Torkar, “Introduction of a process maturity model for market-driven product management and requirements engineering,” Journal of software: Evolution and Process, 24, 83-113, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1002/smr.535

- P. Sawyer, “Packaged software: challenges for RE,” in Sixth International Workshop on Requirements Engineering: Foundations of Software Quality (REFSQ 2000) Stockholm, 2000.

- C. Moon and V. Torossian, “System and method for classification of documents,” ed: Google Patents, 2007.

- D. L. Olson and J. Staley, “Case study of open-source enterprise resource planning implementation in a small business,” Enterprise Information Systems, 6, 79-94, 2012, doi.org/10.1080/17517575.2011.566697

- S. Sawyer, “Effects of intra-group conflict on packaged software development team performance,” Information Systems Journal, 11(2), 155-178, 2001, doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2575.2001.00100.x

- L. Karlsson, Å. G. Dahlstedt, B. Regnell, J. N. och Dag, and A. Persson, “Requirements engineering challenges in market-driven software development–An interview study with practitioners,” Information and Software technology, 49(6), 588-604, 2007, doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2007.02.008.

- T. M. Somers and K. Nelson, “The impact of critical success factors across the stages of enterprise resource planning implementations,” in Proceedings of the 34th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2001, doi: 10.1109/HICSS.2001.927129

- I. Jebreen, “Requirements determination as a social practice: Perceptions and Preferences of novice analysts,” Computer and Information Science, 8(3), 134, 2015, doi:10.5539/cis.v8n3p134