Overcome Discrimination: A Logistic Regression with 10-year Longitudinal Investigation of Emo Kids’ Facebook Posts

Volume 5, Issue 5, Page No 637-644, 2020

Author’s Name: Proud Arunrangsiwed1,a), Yothin Sawangdee2

View Affiliations

1Faculty of Management Science, Suan Sunandha Rajabhat University, Bangkok, 10300, Thailand

2Institute for Population and Social Research, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom, 73170, Thailand

a)Author to whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: proud.ar@ssru.ac.th

Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 5(5), 637-644 (2020); ![]() DOI: 10.25046/aj050578

DOI: 10.25046/aj050578

Keywords: Emo subculture, Facebook, Logistic regression

Export Citations

This study primarily aims to identify the factors that helped emo kids in 2010 move through the emo-identity discrimination and be able to obtain a certain level of achievement. Facebook is the social network that allows users to track friends’ posts back over 10 years. Content analysis was conducted by using two coders to rate 1,432 Facebook posts published during 2010 until 2019, based on the variables: (1) emo-related content, (2) emotion expression, (3) being a part of fandom, (4) the group of fandom, (5) friend(s) and (6) family appearance. The results from logistic regression analysis reveal that past emo kids’ Facebook posts are increasing in the contents about friends, family, and fan objects over time. However, the number of posts with emo music or emo fan object was reduced. Having social support and belonging to social group, like fandom, might help past emo kids overcome the hard time that they had got prejudiced. Future studies should develop a model or existing theory to explain the complexity of individuals’ overlapping identities blended in social networking profiles.

Received: 29 July 2020, Accepted: 25 September 2020, Published Online: 05 October 2020

1. Introduction

Emo is a subculture and a music genre being popular for teenagers in the first decade of 2000s [1]. It was linked to negative deviant behaviors, such as suicide and self-harm [2], [3]. The members of subculture or “emo kids” in those days currently become young adults [4]. However, these people initially experienced music-taste-based discrimination, and they are negatively stereotyped by people in mainstream culture [5], [6]. This study aims to track their social network posts to see the transformation of their identity and the evolution of relationship with family and peers. These would help identify the factors that save these subculture members from unfair prejudice, which result in their well-being in society.

Emo is considered as a subculture because it has its own values, norm, belief, sets of behaviors, and communication patterns [1], [7]. This subculture was spread via online media, such as Facebook, Myspace, and YouTube. The members shared common interest toward emo, punk music, and artists, such as Fall Out Boy, We the Kings, The Academy Is…, Dashboard Confessional, My Chemical Romance, Paramore, Mayday Parade, Taking Back Sunday, Panic! At the Disco, The All-American Rejects, Boys Like Girls, etc. They would not just perform as fans of these artists, but they also need to be able to identify with their music [1], [8]. These fans believe that their favorite songs can help them with difficult life event regarding school and parents. Their common apparels were black T-shirt and skinny jeans, and they usually applied black eyeliner with dyed black hair covering one eye [9], [10]. Emotional expression is acceptable for both female and male ones, e.g., subculture members would comfort a crying emo boy, rather than blaming him regarding the lack of masculinity. As the result of these characteristics, emo boys were often stereotyped by outsiders as gay men, which could cause serious cyberbullying.

Other than the mentioned practices, suicide and self-injury are perceived as important norms of emo subculture [11], [12]. After the suicide of two Australian female students, Jodie Gater and Stephanie Gestier, in 2017, emo kids were not viewed only as subculture members or fans of modern punk music, but folk devils [13], [14]. They used social network and allowed emo texts to alter their thoughts to associate with self-injury and suicidal idea [8], [15]. This contradiction against social norm is the cause that public marked them as deviants rather than a subculture [16], [17]. Mass media have played an important role to create moral panic regarding the link between music taste and anti-social behaviors [18] as they connected the case of Columbine school shooting to metal music [19], [20], and the suicide of two female teenagers to emo music fandom [1], [21]. Although metal fans were initially judged by public that their music taste was related to aggression [19], [22], this group of fans discriminate against emo kids based on similar stereotypes [19], [23]. Metal fans also differentiate themselves from emo teens that they were stronger and more masculine than emo kids [24]. Whether emo boys were straight or had an LGBT identity, they were often prejudiced as gay [23]-[26]. On the other hand, as a part of punk music genre [27], punk musicians, fans, and subculture members have displayed their feminine aesthetic by applying cosmetics and female clothing for long time before the birth of emo music [28], [29]. In other words, how people viewed emo kids as gay or problematic is a kind of the discrimination toward a group.

2. Hypotheses Construction

In aforementioned section, emo is both music genre and subculture, some members or fans of which engage self-mutilation and suicide, while public stereotyped them -as a whole- to be folk devils with aggression against self [30], [31]. Problem music, whether punk, emo, or metal, has been targeted as the cause of negative behaviors [32]. Later, it was found that low self-esteem, not problem music, could directly bring about self-harm [33], and there is no relationship found between problem music use and low self-esteem [34], [35]. This implies that emo music may not be the cause of teens’ suicide and self-harm, but it might be a part of coping process that pushes them through their actual initial life problem, that had diminished their self-esteem or had led them to self-mutilation [36].

While people outside subculture understand that teenagers are reinforced with suicidal thought and self-injury by emo music, emo fan scholars reported that these fans stopped cutting themselves after being coped by such the music [21], [37]. To identify with sad music is a part of coping skills that help people accept and make sense with negative event in their life [38], [39]. Sad emo songs were easily used as coping tools by their fans, since the lyrics are about problems with friends, family, heartbreaking, and loneliness [27], [40], [41]. Moreover, a part of subculture norm is to express emotion and identify with emotional emo songs [1], [8]. This helps construct the hypotheses that prior emo kids may continuously listen to emo music or being emo after the age of emo boom (2010), and they have been likely to express their emotion in their social network posts. Hence, the following hypotheses were formulated.

H1: Emo kids have posted emo-related texts on their social network (Facebook) profile since 2010 (roughly the last year that emo subculture was popular) until 2019.

H2: Emo kids have expressed their emotion in their social network posts since 2010 until 2019.

Although emo music helps teenagers cope with personal troubles, they may not avoid negative stereotype constructed by public. Therefore, it is important to identify the factors that help them walk through this discrimination. Racial discrimination could result in lower self-esteem and higher depression [42], [43]. Parents should not only help their children prepare for being discriminated at school [44], but should also teach them coping skills after ad hominem attack [45]. Other family members and people with similar identity as the victims could also help reduce stress from discrimination and find the way to solve such the problem for the victims [46] – [48]. The above literature could indicate that family and peers might be an important part that saved emo kids from the discrimination. This means emo kids may have lived with their family and communicated with their friends during 2010 to 2019. The particular evidence eventually entails the following hypotheses.

H3: Emo kids have posted texts (alphabetic text, image, or video) about their friends since 2010 until 2019.

H4: Emo kids have posted texts about their family since 2010 until 2019.

However, Strauss [49] stated that self-harm in emo kids was rooted from their lack of social and family support, and this is opposite from H3 and H4. If these adolescents were negatively stereotyped, low in self-esteem, and have lack of social support; being a part of fandom or fanship might be the factor that heightens their self-esteem [50], [51], and allows them to healthily grow up as well as people in mainstream culture [52]. Joining fan community could provide fans with sense of belonging and that brings about self-esteem [53]-[55]. While fans listen to their favorite songs, the music could stimulate their self-esteem [35], especially for metal music fans who extremely believe in ones’ own authenticity [56]. Authenticity refers to having realness value, or freedom of expression regardless others’ attitude or hegemony [57]. Eminem’s authenticity, for instance, is scorn and crudeness [58]. Hall [29] found that emo musicians and also fans accepted their difference apart from outsiders in mainstream culture. This is close to the term of self-concept clarity toward group identity, which is associated with having self-esteem [59], [60]. Recently, it was found that emo fans could earn fan-related self-esteem during attending emo-punk concert [61]. These could derive a hypothesis that emo kids have been part of fandom or fanship whether it is directly about emo music or other objects of interest.

H5: Emo kids have posted texts related to any kind of fandom or fanship from 2010 until 2019.

Because identity can be changed over time [62], [63], to track Facebook posts of past emo kids could help understand their identity transformation related to their fan identification, emotion expression as subculture value, and how they obtain family and peer support. This may help explain how they overcome the discrimination and can live normally as well as general adults.

3. Method

The current study built on the previous study, which reported that emo kids who engaged in emo online community in past 10 years could handle the emo-identity discrimination and grow up and work in proper careers [64]. The current study would track the social network posts of the same group of past emo kids in mentioned study to seek for the factors that may allow them to move pass through the discrimination, and consequently, they could reach their life achievement.

Based on the reviewed articles [37], [46], [48], [51], fan identity, family and peers, and emo music consumption could be the important factors that help emo kids overcome the discrimination and other life problems. Hence, the major variables that would be explored are (1) emo music or emo-subculture-related content in the Facebook post, (2) the level of emotion expression in the post, (3) being fan or being a part of fandom, (4) the group of fandom that the samples belong to, (5) friend(s) and (6) family appearance in Facebook post.

3.1. Samples

Because emo subculture was risen and grown in the Internet [14], data collection of the current study would be done online, as well as earlier studies of Overell [1], and Zdanow and Wright [8]. The cases of these researchers were prepared in the time that emo subculture and music were popular, or around 2006-2010, but for the current study, the data collection was done in 2019. The samples needed to be active social network users since 2010 until 2019. Because people could change their identities over time, to use the continuous-active users could help confirm their original identification as a part of emo subculture.

Therefore, the first researcher of the present study used one’s own Facebook friend list containing emo kids in 2010 as the site for data collection. The majority of samples were white and yellow. Few were from Africa, Middle East, and India. This recruitment method might be the only way to ensure that these users had had emo identity during 2010. Other strategies to recruit the cases might be impossible, because it is hard to know the exact date that users like an emo-related Facebook page or join in a group. For Myspace, although it was the major social network considered as social capital for emo kids in those days, most users have now been inactive [1], [14], [24], [41].

The mentioned friend list had contained more than 300 users, but in 2019, the number of users left in this list is 273. The users who did not post any new post in the latest two months were excluded from the study. Only 62 users were active and selected as the samples. After 62 active users were added into the codesheet, we prepared the codesheet by listing the randomly selected timeline (wall) posts. Twenty-nine posts were chosen from each user. Three posts were selected each year, from 2010 until 2019. The only year with 2 selected posts is 2019, because the data collection was done in July, 2019. The process of the randomization was that each selected post in each year had equally gap of time, which was about 4 months. For instance, if the first selected post was published in early January, the next selected posts would be published in early May and early September, respectively. Therefore, the possible highest number of cases is 1,798. Because some users did not post anything in some month(s), the number of valid cases left for the analysis is 1,432. The 366 cases, which were blank, got removed from the final codesheet.

3.2. Data Collection

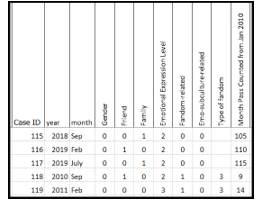

Data collection of the present study was done in Facebook. The raters needed to gather the information from “About” section of profile, and the selected posts in main timeline or wall. These posts could be in many forms, such as text, image, video, link from other websites, and mixing between two or more mentioned types. After codesheet preparation, two raters coded 7 variables as follows:

- Raters could look for this information in “about” part of Facebook profile. Female was coded as 0, and male was coded as 1.

- Emo-music-or-subculture-related content in the post. Raters could consider adding the value into this variable based on text, image, or video in each post. If the media contain emo music, music video, emo apparels, emo facial makeup, and hairstyle, the particular post would be marked as emo-related. Some phases or signs in text were also associated with emo-style discourse, e.g., xoxo, rawr, etc. This variable is for checking if users still have the same identity as they had had 10 years ago. If the post applied to the given condition, the raters would code 1, and 0 for not applied.

- The level of emotion expression in the post. Unlike the previous items, this variable is not dichotomous. If the user did not display any emotion at all, both verbally and nonverbally (use photos, sticker, Facebook mood, or emoticon), the raters would code the post as 0. The small, moderate, and extreme amount of emotion expression were coded as 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

- Friend(s) appearance in Facebook post. If friend(s)’ name(s) was mentioned or tagged in the post, or friend(s)’ photo(s) was published, the raters would code that post as 1. On the contrary, if the post was not related to any friend, it would be coded as 0.

- Family appearance in Facebook post. The coding rule was similar with the previous item. If there are one or more family members in the post, it would be coded as 1, and if not, it would be coded as 0.

- Being fan or being a part of fandom. Whether the user displayed oneself as emo fan or fan of other media object, the post would be coded as 1, and if the post has nothing to do with any fandom or idol, it would be coded as 0. It might be important to note that fandom-related posts could be a shared official post by their favorite artist, photos of artists, album cover, shared news, and also fan art or fan Photoshop manipulation.

- The group of fandom that the samples (each of their posts) belong to. If the previous item, “being fan or being a part of fandom,” were coded as 0, the raters would leave this part of codesheet blank. If the raters found that the post was related to emo fandom, it would be coded as 0. If metal, death metal, or melodic death metal music was found in the post, it would be coded as 1. If the post was about pop or R&B music, it would be coded as 2. If the post was about sport, movie, Japanese anime/manga, games, and politic or government, it would be coded as 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 respectively. Posts about politics and government could be considered as fandom-related posts, because it consists of the acts of fan and anti-fan, to support or to protest against some policy. Moreover, Bronstein [65] discovered that many people treated politicians the same way as they treated celebrities, and vice versa. Politicians could post non-politic-related photos, such as vacation with their family, and their supporters also commented and shared the posts.

Another variable is the number of month(s) counted from the beginning of 2010. This variable is the major predictor in all regression models. If the post was published in March, 2010, for instance, the value of this variable would be 3. If the post was published in February, 2011, the value will be 14. Hence, the smallest possible value is 1 month, and the highest is 115 (9 years and 7 months).

Figure 1: Codesheet preparation

3.3. Analysis

Most parts of the data were presented using descriptive statistics. Logistic regression analysis was used to understand the probability of the variables, emo-music-or-subculture-related contents, being a part of fandom or fanship, friend(s), and family appeared in posts over time during 2010 to 2019. This implies that in the analysis, independent variable is the number of month counted from the beginning of 2010, and the dependent variables are all 4 mentioned dichotomous variables. At the same time, linear regression analysis was used to understand the effect of passing time on the level of emotion expression in social network post.

Because logistic regression analysis was employed for data analysis, the rated values of dichotomous variables cannot be averaged. There were 24 cases with disagreement, so the values of one rater were chosen to paste in final codesheet.

4. Findings

To answer if these past emo kids still listen to emo music or having emo identity (H1), the findings show that there are 341 posts related to emo music and emo subculture from 2010 until 2019. These are 23.8 percent of all post (n=1432), as presented in Table 1. However, lately, the number of this kind of post had been slightly decreased (Odds Ratio=.995; p=.006), especially in last 4 years (2016-2019).

According to Table 1. it is noticeable that some groups of variables are overlapping, and the most overlapping cases are between the groups, fandom and emo-related posts (n=150), and following by the overlapping of fandom, emo-related posts, and friend appearance in posts (n=33).

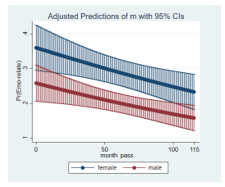

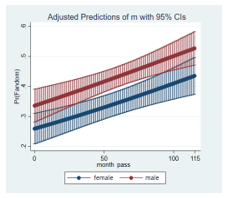

As shown in Figure 2., both male and female tracked emo kids have similar decreasing tendency in posts related to emo music and subculture, and women generally have higher numbers of this kind of posts than men. It was interesting to look into the demographic data regarding gender. After checking carefully in these 62 selected users, there are only two genders appearing which are female and male. Based on these 1432 cases, 570 cases were posts by female users, and 862 cases were posts by male users. This offers an opportunity for future researchers to understand more about emo masculinity. Men, who are emo or were previously emo, may not have an LGBT identity, but with the subculture value, it allows men to display their feminine characteristics.

Table 1: Frequency of, and friend-and-family-related posts,

fandom-related post, and emo-related posts

| Friend Appearance | Family Appearance | Fandom-related | Emo-related | n | percent |

| ✓ | – | – | – | 154 | 10.75% |

| – | ✓ | – | – | 83 | 5.80% |

| ✓ | ✓ | – | – | 13 | 0.91% |

| – | – | ✓ | – | 343 | 23.95% |

| ✓ | – | ✓ | – | 27 | 1.89% |

| – | ✓ | ✓ | – | 8 | 0.56% |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | 1 | 0.07% |

| – | – | – | ✓ | 122 | 8.52% |

| ✓ | – | – | ✓ | 22 | 1.54% |

| – | ✓ | – | ✓ | 4 | 0.28% |

| – | – | ✓ | ✓ | 150 | 10.47% |

| ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | 33 | 2.30% |

| – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | 0.35% |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | 0.35% |

| – | – | – | – | 462 | 32.26% |

| 255 | 119 | 572 | 341 | 1432 | 100% |

| 17.81% | 8.31% | 39.94% | 23.81% | 100% |

Figure 2: Margins plots for emo-related posts

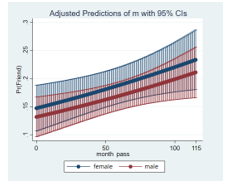

Figure 3: Margins plots for friend-related posts

Although emo media consumption and identification toward subculture were somewhat reduced, they still have emo core value, which is vulnerability (H2). Many posts were high in emotion expression until 2019 (Mean=1.661; S.D.=1.129). The linear regression reveals no difference in the level of emotion expression in the post over time (F=3.595; R2=.003; Beta=-.050), but with small decreasing lately.

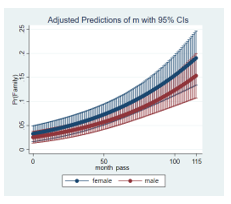

Figure 4: Margins plots for family-related posts

Figure 5: Margins plots for fandom-related posts

Unlike the expectation (H3, H4), these tracked emo kids rarely posted text and photos about their family and friends. Table 1. shows that there are only 17.8 percent of posts containing text, image, or video related to friend(s), and only 8.3 percent related to family. Based on the results of logistic regression in Table 2., only small increasing in friend-related posts was found (OR=1.005; p=.022), while there is a strong significant increasing of family-related posts (OR=1.017; p=.000). As seen in Figure 3. and 4., there is an actual increasing of friend and family contents in their Facebook posts. Women are higher in these types of posts them men. This could be because women have more willingness to disclose personal information in social network than men [66]. This might be related to gender norm and social acceptance that women can freely display their friendship, intimacy, and relationship with their family and peers.

Table 2: Univariate logistic regression

with the number of month counted from the beginning of 2010 as the predictor.

| Dependent Variables | Emo–Related | Friend(s) | Family | Fandom |

| Overall OR (95%CI) |

.995** (.991-.998) |

1.005* (1.001-1.009) |

1.017*** (1.011-1.023) |

1.007*** (1.004-1.010) |

| Female OR (95%CI) |

.996 (.990-1.001) |

1.006 (.999-1.012) |

1.014** (1.005-1.024) |

1.011*** (1.006-1.017) |

| Male OR (95%CI) |

.994* (.989-.999) |

1.004 (.999-1.010) |

1.019*** (1.010-1.028) |

1.004* (1.000-1.008) |

| Overall OR (95%CI) Controlled by Gender |

1.005** (1.002-1.009) |

.995* (.991-.999) |

.983*** (.977-.989) |

1.445*** (1.159-1.800) |

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001, n=1,432, n female=570, n male=862

The examples of family members found during the coding are wife, husband, grandmother, and uncle. The later marriage might be the reason that the number of family-related posts are lately greater. After reviewing the actual data, it could also be noticed that some who were married often changed their music taste and group of fandom to match their life partner.

For the fifth hypothesis (H5), these past emo kids belong to groups of fandom, whether it is emo music or other kind of media object fandom. This means that these people have had their fan identity for entire 10-year period tracked in the current study. The frequency of posts related to each group of fandom was presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Frequency of the posts

shown the groups of fandom which the cases belong to

| Belonging to fandom | Number of Posts | Percent | |||

| Emo music | 266 | 46.50 | |||

| Metal/Death Metal | 20 | 3.50 | |||

| Pop or R&B | 140 | 24.48 | |||

| Sport | 66 | 11.54 | |||

| Movie | 62 | 10.84 | |||

| Japanese anime/manga | 48 | 8.39 | |||

| games | 63 | 11.01 | |||

| politic or government | 37 | 6.47 | |||

| Total (with overlapping cases) | 702 | 112.731 | |||

| Total (all fandom-related post) | 572 | 100.00 | |||

1 The percentage is over 100, because some posts contained more than one type of fandom-related content.

Around 2013-2019, they posted texts and images about their fan objects more frequent than the first 3 years, as shown in Figure 5. Most of them still prefer emo music and bands until 2019, but they have also belonged to more groups of fandom. Like, after the first year, 2010, many of them started to listen to softer music, like pop and R&B. At the same time, some of them were interested in games, and Japanese comics and animation. Some showed that they have started to watch sport matches since 2015, such as soccer and American football. Similarly, some began to be interested in famous movies and Hollywood actors in 2015. In late 4 years, 2016-2019, some turned themselves to be the fans of politic. These past emo kids might increase their online civic engagement because they got older.

5. Discussion and Suggestion

As shifting away from the findings and suggestions of various studies that family plays an important role to solve the problem regarding discrimination in teenagers and students [45], [46], [48], the current study indicates that family and friends may not be a prominent factor that helps emo kids overcome the discrimination. This is because there had been lack of family-and-friend-related Facebook posts, especially at the beginning of the tracked period, 2010-2019. It is necessary to note that emo-identity discrimination had been peak at the beginning of the time period. One observation that can be explained this issue is that at the time that they got discriminated or cyberbullied, they may get lack of family support. Therefore, this part of findings suggests that it was other factor(s) that helps them overcome the discrimination.

Since the current study was conducted with content analysis and the cases were the public posts on Facebook, it might yield some imprecise data. Many emo kids, back in those days, were teenagers, and most of them might live with their parents and communicate with them, but they might not need to show the photos of their parents in online space where other members of emo subculture would see. Like, middle school students do not want their parents to show up at school, because they may want to look independent and confident [67]. Therefore, these samples, with high-school age (around 2010), may not want to show their family on Facebook, too. To choose only one right conclusion among the finding (H3, H4) and this assumption that emo kids might live with parents in early 2010s, the in-depth interview should be employed in future studies.

Supported by numerous fan studies [50], [51], [56] and psychological studies [52], [68], these tracked emo kids may be able to move pass though the obstruction regarding discrimination, because they have been a part of fandom(s) (H5). Because fan activities [69], fans’ media consumption [50], and sense of belonging in fan community [55] have a significant impact on fans’ self-esteem, these emo kids may obtain the self-esteem from these fan-related factors. To have high self-esteem, people will be low in depression, and high in many positive life outcomes [52], [70].

Listening to emo music and identifying with it is also a kind of coping skills [21], [37]. Emo kids who faced negative life events were mentally healed by listening to emo music [21], [37]. The result of this study reveals that the tracked emo kids have continuously consumed emo music and expressed their emo identity (H1). Emo music might be the factor that helps them overcome the discrimination. It might be unusual to conclude that emo fans were prejudiced because of their music taste, and they could overcome the discrimination because of listening to emo music. An alternative suggestion is that fans used emo music as a part of coping process according to serious event in their real life. To be discriminated online might become small issue compared to the main problem they had had. This could be supported by the finding of Hall [29] that emo artists understood and showed the difference between emo subculture members and outsiders. Moreover, listening to ones’ favorite music could help heighten self-esteem [35], so if emo fans were high in self-esteem strongly toward music and their subculture, the external factor might not be able to harm them.

Because emo kids have not only communicated with only people in the same subculture, it is still important to understand how they communicated with other people. Emo music and its fandom have been great parts of emo subculture. Fan communication may be able to help explain the practice in emo subculture. Fans normally communicated to 4 groups of people regarding their fan object and identity, which are (1) in-group members with the same identity, (2) hegemony, – or in this case is emo artists and emo bands, – (3) general out-group members, e.g. the friends and parents, and (4) out-group members who are their enemy, like people who discriminated against them [71].

To explain emo subcultural identity and their communication pattern might be somewhat complex. In Facebook or other social networking system (SNS) blends together many contexts people live in, in their real life. A Facebook friend might be an in-group member of emo subculture, but one might be an out-group member of workplace context. Future researchers may try to use social identities theory to explain all these complexities of the way many identities of an individual are mixed and blended in single SNS profile.

In the current study, the findings allow us to see the transformation of the identity from one to the others, from emo fans to other types of fandom, from young adolescents to adults with family and larger group of friends, and especially from vulnerable teenagers to stronger mature people.

Engaging in fandom might be the most important factor that helps emo kids move forward the discrimination, while the overall result could suggest that the way they move on and the transformation of their identity may be developed alongside with one another. Social network does not only help scholars to understand a subculture, but it actually helps and individual to see their developing identity, help them to understand themselves better, and that might be a part of how they move forward from discrimination, too.

An unexpected finding beside the major part of hypothesis testing is that many emo kids in 2010 had left their Facebook accounts, which causes a lot of missing cases in the present data sheet. Burke [72] found that many graduate students left their Facebook profile and signed up for other SNS such as LinkedIn because they need to look more professional, and some needed to switch to use other SNS to match their colleagues’ choice.

The identity as an emo subculture member cannot be considered as a professional. Instead of editing the existing Facebook profile, some may choose to create a new profile. With the same group of samples but earlier study [64], many of them have worked in professional occupation such as, teachers, lecturers, engineers, designers, and some are entrepreneur of real estate business. In other words, while some people decided to leave their Facebook profile, some chose to continue using the same profile, but they turned it from an emo profile to be an expert one.

Even though the data of this study may consist of selection bias, we could learn that social network is an important part to spread, support, and maintain many subcultures, and one of these is emo subculture. We could see emo kids through their social network profiles that they have grown up to be young adults, used social capital in order to overcome the discrimination, coped with possible depression, and finally adjusted their life as subculture members to fit into the world complex society. Future study should continue looking at these emo kids’ identity development and communication pattern through their adulthood and older adult ages. This way could help understand the strategies to achieve the long-term well-being of people who had experienced taste-and-identity-based discrimination.

6. Limitations

The major limitation of the present study is the small number of samples, which is 62 users. This may not be comparable to the actual population or emo kids before 2010. Moreover, these 62 users are the researcher’s online friend, which might not represent general emo kids. Additionally, the data collection was content analysis done in online space, Facebook, where people may construct another identity such as ideal-self.

To solve this issue, researchers of future studies should hire computer experts to recruit more prior emo kids in 2010 who are still active on social networking today. This would help increase sample size and strengthen the statistical conclusions of the current study. It is also important to note that many genders are available for Facebook users to choose. Therefore, samples with LGBT identity and asexual should be also included in future studies. As a result of this, the particular research would achieve a better generalization.

- R. Overell, “Emo online: networks of sociality/networks of exclusion,” Perfect Beat, 11(2), 141–162, 2010, doi: 10.1558/prbt.v11i2.141.

- M. Definis-Gojanović, D. Gugić, D. Sutlović, “Suicide and Emo youth subculture–a case analysis,” Collegium antropologicum, 33(2), 173–175, 2009.

- R. Young, N. Sproeber, R.C. Groschwitz, M. Preiss, P.L. Plener, “Why alternative teenagers self-harm: exploring the link between non-suicidal self-injury, attempted suicide and adolescent identity,” BMC psychiatry, 14(1), 137, 2014, doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-137.

- K. Moulton, Dashboard Confessional’s Chris Carrabba Refuses to Age Out of Emo. Westword, (2018). Retrieved from https://www.westword.com/music/dashboard-confessionals-chris-carrabba-wont-age-out-of-emo-10161529

- S.J. Minton, Alterophobic bullying and violence. in J.L. Ireland, P. Birch, C.A. Irland, (eds.), The Routledge International Handbook of Human Aggression: Current Issues and Perspectives, Routledge, 2018, ISBN: 978-1-315-61877-7.

- D. Hernández-Rosete, “Bullying of emos in Mexico City: an ethnographic analysis,” Cadernos de Saude Publica, 33(12), 2017, doi: 10.1590/0102-311×00080116.

- T.D. Baker, S. Smith-Adcock, V.R. Glynn, “The Ghost of Emo: Searching for Mental Health Themes in a Popular Music Format,” Journal of School Counseling, 11(8), 1–35, 2013.

- C. Zdanow, B. Wright, “The representation of self-injury and suicide on emo social networking groups,” African Sociological Review/Revue Africaine de Sociologie, 16(2), 81–101, 2012.

- M. Heřmanský, There and Back Again: Linking Online and Offline Spaces in/of Czech Emo Subculture. in Hebdige and Subculture in the Twenty-First Century (pp. 169-205), Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2020.

- C.U. Gielis, It’s not a fashion statement. An exploration of masculinity and femininity in contemporary emo music, Master thesis, Radboud University, 2018.

- P. Arunrangsiwed, R. Arunrangsiwed, Stereotyped Emo Kids: A literature review. in The 4th Technology Innovation Management and Engineering Science International Conference (TIMES-iCON), IEEE, 2019, doi: 10.1109/TIMES-iCON47539.2019.9024586.

- C. Partridge, Suicide, Angst, and Popular Music, Coward-Gibbs, M. (Ed.) Death, Culture & Leisure: Playing Dead (Emerald Studies in Death and Culture), Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 189-208, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83909-037-020201020.

- M. Phillipov, “Just emotional people? Emo culture and the anxieties of disclosure,” M/C Journal: A Journal of Media and Culture, 12(5), 2009.

- M. Phillipov, “Generic misery music? Emo and the problem of contemporary youth culture,” Media International Australia, 136(1), 60–70, 2010, doi: doi.org/10.1177/1329878X1013600109.

- R. Trnka, M. Kuška, K. Balcar, P. Tavel, “Understanding death, suicide and self-injury among adherents of the emo youth subculture: A qualitative study,” Death studies, 42(6), 337–345, 2018, doi: 10.1080/07481187.2017.1340066.

- M.D. Daschuk, It’s not a fashion statement, it’s a death wish: subcultural power dynamics, niche-media knowledge construction, and the emo kid folk-devil, Master’s thesis, University of Saskatchewan, 2009.

- S.F. Williams, “A walking open wound: Emo rock and the “crisis” of masculinity in America,” in F. Jarman-Ivens (Ed.), Oh Boy! Masculinities and Popular Music (pp. 153–168). Taylor & Francis Group, 2013.

- R. Burns, C. Crawford, “School shootings, the media, and public fear: Ingredientsfor a moral panic,” Crime, law and social change, 32(2), 147–168, 1999.

- M.A. Miernik, “The evolution of emo and its theoretical implications,” Polish Journal for American Studies, 7, 175–188, 2013.

- G.W. Muschert, “Frame-changing in the media coverage of a school shooting: The rise of Columbine as a national concern,” The Social Science Journal, 46(1), 164–170, 2009, doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2008.12.014.

- R. Haydn, My Chemical Romance: This Band Will Save Your Life, Plexus Publishing, 2015.

- C. Baker, B. Brown, “Suicide, self-harm and survival strategies in contemporary heavy metal music: a cultural and literary analysis,” Journal of medical humanities, 37(1), 1–17, 2016, doi: 10.1007/s10912-014-9274-8.

- R.L. Hill, “Is Emo Metal? Gendered Boundaries and New Horizons in the Metal Community,” Journal for cultural research, 15(3), 297–313, 2011, doi: 10.1080/14797585.2011.594586.

- K. Schmitt, Exploring dress and behavior of the emo subculture. Master’s thesis, Kennesaw State University, 2011.

- H.T. Sternudd, A. Johansson, The girl in the corner: Aesthetics of suffering in a digitalized space, in L.G. Guerra, and J.A. Nicdao (Eds.), Narrative of Suffering: Meaning and Experience in a Transcultural Approach (pp. 105–115). Inter-Disciplinary Press, 2014.

- B.M. Peters, “Emo gay boys and subculture: Postpunk queer youth and (re) thinking images of masculinity,” Journal of LGBT Youth, 7(2), 129–146, 2010, doi: 10.1080/19361651003799817.

- B. Bailey, Emo Music and Youth Culture. in S. Steinberg, P. Parmar, B. Richard (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Contemporary Youth Culture, Greenwood Press, 2005.

- C.A. Aberle, Serious is Bad: A Queer Reading of Punk, Midwest Emo, and Connecticut DIY, Honors thesis, Wesleyan University, 2019.

- N. Hall, Representations of the Outsider in David Bowie’s Glam Period and its Continuation through Punk, Goth, and Emo: Thematic, Aesthetic, and Subcultural Considerations, Master’s thesis, University of Ottawa, 2015.

- M. Chęć, A. Potemkowski, M. Wąsik, A. Samochowiec, “Parental attitudes and aggression in the Emo subculture,” Psychiatria polska, 50(1), 19–28, 2016, doi: 10.12740/PP/36316.

- M.A. Hughes, S.F. Knowles, K. Dhingra, H.L. Nicholson, P.J. Taylor, “This corrosion: A systematic review of the association between alternative subcultures and the risk of self-harm and suicide,” British journal of clinical psychology, 57(4), 491–513, 2018, doi: 10.1111/bjc.12179.

- J. Lozon, M. Bensimon, “Music misuse: a review of the personal and collective roles of problem music,” Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19(3), 207–218, 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2014.04.003.

- A.C. North, D.J. Hargreaves, “Problem music and self-harming,” Suicide and life-threatening behavior, 36(5), 582–590, 2006, doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.5.582

- E. Bodner, M. Bensimon, “Problem music and its different shades over its fans,” Psychology of Music, 43(5), 641–660, 2015, doi: 10.1177/0305735614532000

- J. Kneer, D. Rieger, “The memory remains: How heavy metal fans buffer against the fear of death,” Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 5(3), 258, 2016, doi: 10.1037/ppm0000072.

- L. Meono, Using music-based interventions with adolescents coping with family conflict or parental divorce: A resource manual, Ph.D. Thesis, Pepperdine University, 2015.

- R. Hill, Emo saved my life: challenging the mainstream discourse of mental illness around My Chemical Romance, in Can I Play With Madness? Metal, Dissonance, Madness and Alienation (pp. 143–153), Inter-Disciplinary Press, Oxford, 2011.

- A.J. van den Tol, “The appeal of sad music: A brief overview of current directions in research on motivations for listening to sad music,” The Arts in Psychotherapy, 49, 44–49, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2016.05.008.

- A.J. van den Tol, J. Edwards, N.A. Heflick, “Sad music as a means for acceptance-based coping,” Musicae Scientiae, 20(1), 68–83, 2016, doi: 10.1177/1029864915627844.

- T. Kelley, L. Simon, Everybody hurts: An essential guide to Emo culture. Harper Collins, 2007.

- R.A. Tanjung, The Commodified Emo Subculture In America Through The Used’s Music Videos, Ph.D. thesis, Sebelas Maret University, 2011.

- E.H. Mereish, H.S. N’cho, C.E. Green, M.M. Jernigan, J.E. Helms, “Discrimination and depressive symptoms among Black American men: Moderated-mediation effects of ethnicity and self-esteem,” Behavioral Medicine, 42(3), 190–196, 2016, doi: 10.1080/08964289.2016.1150804.

- T. Yip, “The effects of ethnic/racial discrimination and sleep quality on depressive symptoms and self-esteem trajectories among diverse adolescents,” Journal of youth and adolescence, 44(2), 419–430, 2015, doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0123-x.

- C.D. Presseau, Racial Discrimination and Mental Health for Transracially Adopted Adults: The Roles of Racial Identity and Racial Socialization, Ph.D. thesis, Lehigh University, 2016.

- S.M. Schires, N.T. Buchanan, R.M. Lee, M. McGue, W.G. Iacono, S.A. Burt, “Discrimination and ethnic-racial socialization among youth adopted from South Korea into white American families,” Child development, 91(1), e42–e58, 2020, doi: 10.1111/cdev.13167.

- M. Banerjee, J.S. Eccles, Perceived racial discrimination as a context for parenting in African American and European American youth, in H.E. Fitzgerald, D.J. Johnson, D.B. Qin, F.A. Villarruel, and J. Norder (Eds.), Handbook of Children and Prejudice (pp. 233–247), Springer, 2019.

- L.A. Leslie, J.R. Smith, K.M. Hrapczynski, D. Riley, “Racial socialization in transracial adoptive families: Does it help adolescents deal with discrimination stress?,” Family Relations, 62(1), 72–81, 2013.

- M. Svetaz, “Tips to help teen patients deal with discrimination,” Family practice management, 23(4), 44, 2016.

- E. Strauss, Early adolescent boys’ perceptions of the Emo youth subculture, Ph.D. Thesis, North-West University, 2012.

- J. Phua, “Consumption of sports team-related media: Its influence on sports fan identity salience and self-esteem,” in Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association (Vol. 21), 2008.

- Y.C. Rhee, J. Wong, Y. Kim, “Becoming sport fans: Relative deprivation and social identity,” International Journal of Business Administration, 8(1), 118–134, 2017, doi: 10.5430/ijba.v8n1p118.

- U. Orth, R.W. Robins, K.F. Widaman, “Life-span development of self-esteem and its effects on important life outcomes,” Journal of personality and social psychology, 102(6), 1271–1288, 2012, doi: 10.1037/a0025558.

- P. Arunrangsiwed, C.S. Beck, “Positive and Negative Lights of Fan Culture,” Suan Sunandha Rajabhat University Journal of Management Science, 3(2), 40–58, 2016.

- H. Jenkins, Textual poachers: Television fans and participatory culture, Routledge, 2012, ISBN: 9780203114339.

- D.L. Wann, J. Hackathorn, M.R. Sherman, “Testing the team identification–social psychological health model: Mediational relationships among team identification, sport fandom, sense of belonging, and meaning in life,” Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 21(2), 94–107, 2017, doi: 10.1037/gdn0000066.

- R.E.S. Breen, We Mean It Maaan: Deconstructing Authenticity in the Punk and Metal Discourse, Master’s thesis, Wesleyan University, 2017.

- M. Corciolani, “How do authenticity dramas develop? An analysis of Afterhours fans’ responses to the band’s participation in the Sanremo music festival,” Marketing Theory, 14(2), 2014, doi: 10.1177/1470593114521454.

- E.G. Armstrong, “Eminem’s construction of authenticity,” Popular Music and Society, 27(3), 335–355, 2004, doi: 10.1080/03007760410001733170.

- J.D. Campbell, P.D. Trapnell, S.J. Heine, I.M. Katz, L.F. Lavallee, D.R. Lehman, “Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries,” Journal of personality and social psychology, 70(1), 141–156, 1996.

- J. Wu, D. Watkins, J. Hattie, “Self-concept clarity: A longitudinal study of Hong Kong adolescents,” Personality and Individual Differences, 48(3), 277–282, 2010, doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.10.011.

- P. Arunrangsiwed, P. Lekyan, “Being Unique does not make an Identity Conflict: A Narcissistic Fan of Mayday Parade,” in The 6th International Conference on Management Science, Innovation and Technology, 2019.

- B.R. Johnson, G. Duwe, M. Hallett, J. Hays, S.J. Jang, K.R. Kerley, Faith and Service: Pathways to Identity Transformation and Correctional Reform. in K. R. Kerley (Ed.), Finding Freedom in Confinement: The Role of Religion in Prison Life (pp. 3–23), ABC-CLIO, 2018.

- N.L. Young, “Identity trans/formations,” Annals of the International Communication Association, 31(1), 250–299, 2007, doi: 10.1080/23808985.2007.11679068.

- P. Arunrangsiwed, K. Utapao, P. Bunyapukkna, K. Cheachainart, N. Ounpipat, “Emo Myth: 10-Year Follow-Up Stereotype Test of Emo Teens in 2000s,” in International Conference on Innovation, Smart Culture and Well-Beings (ICISW2018), Bangkok, Thailand, 2018.

- J. Bronstein, “Like me! Analyzing the 2012 presidential candidates’ Facebook pages,” Online Information Review, 37(2), 173-192, 2013, doi: 10.1108/OIR-01-2013-0002.

- N.R. Raselekoane, T.J. Mudau, P.P. Tsorai, “Gender differences in cyber-bullying among first-year University of Venda students,” Gender and Behaviour, 17(3), 13848-13857, 2019, ISSN: 1596-9231.

- L. Bailey, “Parental Involvement and Student Achievement: A Review of the Literature,” Culminating Experience Action Research Projects, 6, 19-44, 2004, doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-28064-6_2.

- J.F. Sowislo, U. Orth, “Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies,” Psychological bulletin, 139(1), 213–240, 2013, doi: 10.1037/a0028931.

- K. Bahoric, E. Swaggerty, “Fanfiction: Exploring in-and out-of-school literacy practices,” Colorado Reading Journal, 26, 25–31, 2015.

- A.A. Gardner, C.A. Lambert, “Examining the interplay of self-esteem, trait-emotional intelligence, and age with depression across adolescence,” Journal of adolescence, 71, 162–166, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.01.008.

- P. Arunrangsiwed, R. Komolsevin, C.S. Beck, “Fan Activity as Tool to Improve Learning Motivation,” Suan Sunandha Rajabhat University Journal of Management Science, 4(2), 16–32, 2017.

- V.C. Burke, Email is Alive: How to Communicate with Graduate College Students, Doctoral thesis, UNLV, 2019.

Citations by Dimensions

Citations by PlumX

Google Scholar

Scopus

Crossref Citations

No. of Downloads Per Month

No. of Downloads Per Country